Happy… worm day!?

Japan’s “micro-seasons” make every week a little celebration

I’ve heard some foreigners bristle when asked by Japanese if they have four seasons in their country. The question, so common as to be trite, is easy to misinterpret as Japanese thinking their nation is special in this regard. But I don’t think it is intended that way. It’s more like, “do you celebrate the seasons in the way we do?” And we celebrate them. We really, really do. Not just four, either. Those are just the broadest distinctions. There are many gradations in between.

Much of Japanese art and culture is built upon seasonality, from traditional foods and fashions to poetry and the “Zen arts” such as flower arrangement and tea ceremony. The cherry blossom season is perhaps the most famous abroad, but it is only one example.

We open letters with set phrases acknowledging the seasons. We eat with the seasons. Shojin-ryori “devotional cuisine,” intended for Buddhist monks but widely served to laypeople at temples and specialty shops, is a vegan menu consisting of dishes made from vegetables available at that particular time. Wagashi, Japanese sweets, are lovingly crafted and displayed according to the time of year. And traditional clothing is closely associated with the seasons, too.

My hobby is wearing kimono, the patterns of which are picked to match the calendar: snowflakes for winter, or green maple leaves for early May, for example. Some are even more specific. One of my favorite obi belts features a beautiful rose in bloom, intended to be worn only when the real flowers are blooming themselves. Selecting a kimono to match the season is traditional fashion etiquette. But it is more than just style: recognizing subtle changes in the environment is an opportunity to punctuate daily life with little celebrations.

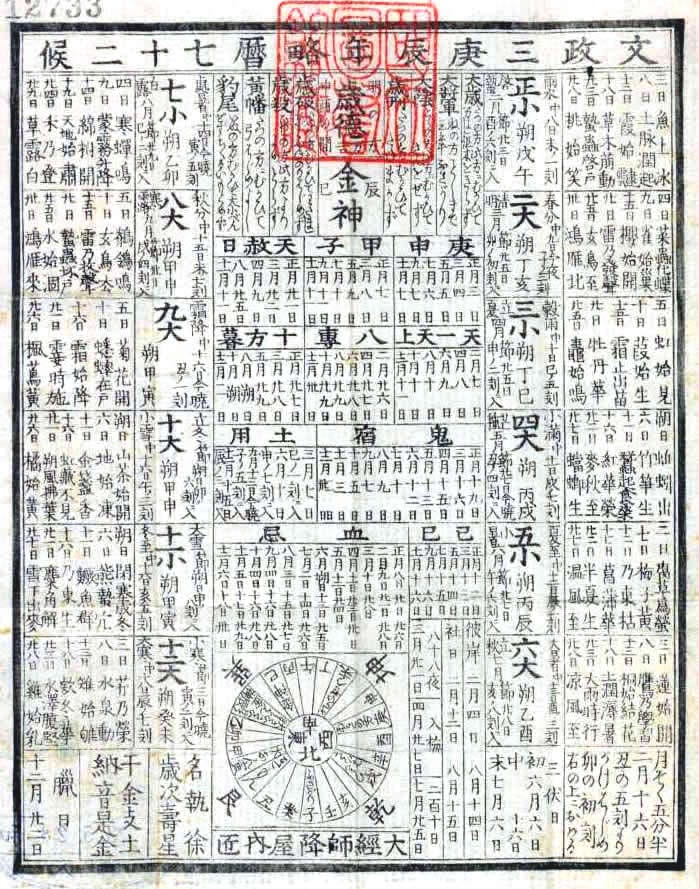

Japanese have long paid close attention to the seasons, but we really codified it with a special calendar that was introduced in 1685. Today, like most of the world, we rely on the Gregorian calendar for daily life. But we only adopted it quite recently, in the 19th century. Before that, we used another calendar that used descriptions of natural phenomena to denote times of year. It is called the Shichijuni-ko, which might be translated as “the seventy-two micro seasons.”

It was adapted from a similar one imported from China, adjusted to fit the local environment by astrologer-astronomers. Their close watch over the sun and stars also made them experts on the seasons. This calendar divides the year into seventy-two segments, each about five days long, which map to regular changes in the patterns of nature, such as the behavior of insects, birds, plants, and changes in weather.

The period which corresponds to May 10th-14th on the Gregorian calendar is called 蚯蚓引, mimizu izuru: “earthworms emerge from the ground.” This one threw me for a loop when I first learned of it, years back. Earthworms? Isn’t that kind of obscure? But then I realized I was thinking like a city girl. And when I thought some more, I noticed it was true. We get a lot of spring showers this time of year, and it isn’t at all uncommon to see confused earthworms trying to crawl across some patch of asphalt.

“Earthworms emerge from the ground” means that the temperature has risen enough for worms to wake from hibernation and start becoming active again. Their movement through the soil makes it soft and fertile, which in turn helps plants grow. Plants are visible, making it easy to appreciate their beauty. But this micro-season is a reminder that beauty is more than just skin deep. Beneath the surface, all sorts of things are supporting that visual allure, chief among them healthy soil, which is the creation of the lowly earthworm. So the micro-season celebrating these gentle little workers, normally toiling out of sight and mind, reminds us to be thankful for their efforts, and their very real impact on our lives.

The calendar of the 72 micro-seasons is full of fun little moments like this, and I’m looking forward to exploring more of them in the future. It’s easy to dismiss the old calendar as irrelevant to modern lives. I mean, it’s tough to schedule a meeting around the sight of earthworms emerging from the soil. But I still find it enjoyable to consult the Shichijuni-ko in my modern life. It fosters a certain sense of belonging that the Gregorian calendar lacks. Referring to the Shichijuni-ko reminds me that we humans are part of the natural system, just like every living thing on this planet. We can’t live without supporting each other. So!

A very happy earthworms-emerge-from-the-ground to you and yours!

Great stuff! I get a weekly email from https://www.spoon-tamago.com/ that I like a lot and they are always talking about micro-seasons but I'd never known the background on it until now, thanks!

I looked up the microseasons in wikipedia, they are so specific and I think this is very moving. People in farming cultures always have a very, very keen sense observing nature, and this was necessary since they were so dependend on it. Plant your plants at the wrong time - they will die - you'll run out of food.

Living in Europe, our "microseasons" are quite different, but it would be a worthwhile attempt to explore the microseasons here. At the moment, it seems to be "first zucchini flowers appear" time of the year in my garden. :-)