Precious Days

Mariya Takeuchi’s new album is a lens into the golden era of J-pop

“You want a physical copy?” asked my husband, a little incredulously.

His finger hovered over the mouse button, ready to click and download an album. That was the usual way we listened to music: purchasing it digitally or by streaming it over his computer, for it’s hooked up to a really nice pair of speakers, much nicer than the ones on my faithful old machine. But not this time. He spun around, looking at me like some kind of caveman.

“Like… a compact disc?” he repeated, as though it were a stone-age tool.

“But it’s Mariya Takeuchi,” I said. “She’s the symbol of my teenage years in the Eighties! I have to buy a physical copy. The last time I bought one of her albums was on cassette!” And so I made the click, on Amazon Japan, and that’s how Mariya Takeuchi’s latest album Precious Days arrived at my door. As I dug around for a CD player to play it, I started thinking of my long association with her music.

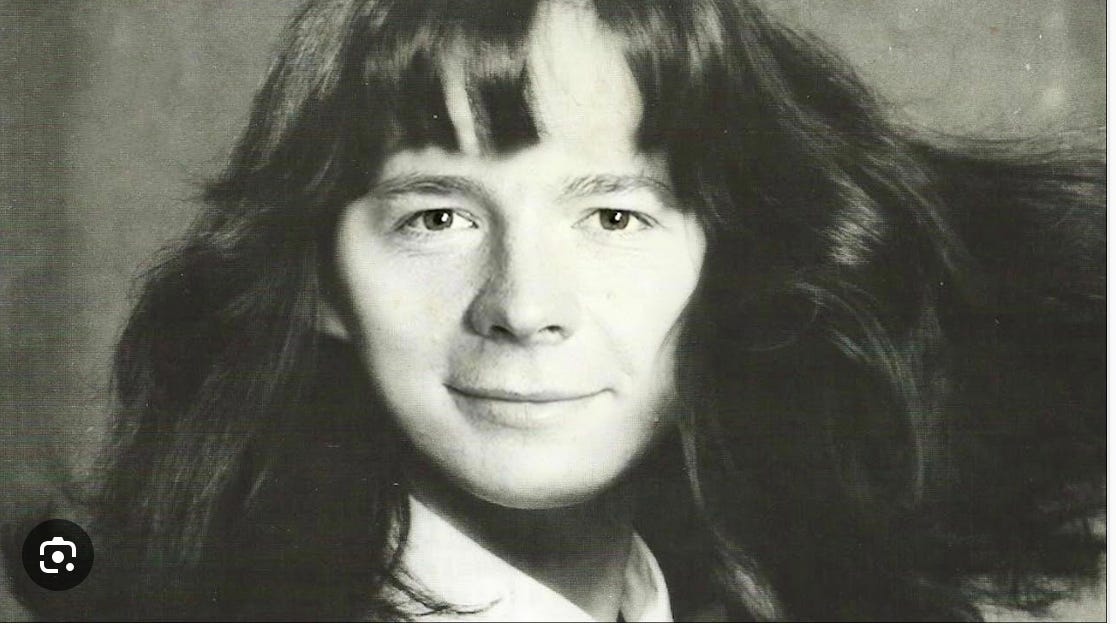

The 1980 megahit single “Fushigi na piichi pie” (The Mysterious Peach Pie) made Mariya Takeuchi a superstar in Japan. But it wasn’t until 1987 that I really started listening to her, after the release of another hit single “Eki” (Station), which she wrote and sang.

It was about a woman who catches a glimpse of her ex at a train station on a rainy day, sparking wistful memories about love and loss. The first time I heard it was as a teenager, on the shiny red Sony radio-cassette deck I kept in my bedroom. The soft voice and gentle tune sounded so soothing to my ears, while the lyrics about the dramas of womanhood enchanted me. It was love at first listen. When I found out that a friend owned a cassette, I was overjoyed. I borrowed it, brought it home, slotted it in my little stereo’s twin tapedecks, and dubbed it right away. Then, to really set the Eighties scene, I popped it into my Walkman.

The 80s were a golden era for J-pop. Looking back, it’s amazing how much of a role music played in our lives: big music shows on primetime TV, J-Wave on the radio (I still recall the channel, 81.3 FM!) Technology played a key role, too. LP records gave way to cassettes; the Walkman let us carry our music out into the world with us, and karaoke was just starting to become a thing, too.

My sense is that outside of Japan, “J-Pop” is used as a synonym for Japanese pop music as a whole. This isn’t necessarily wrong, but for those of us who lived through the golden days, it feels a little too broad. Before sitting down to write this I’d never really thought about how to define J-pop before, because it was always just there, and nobody outside Japan paid a lot of attention to it anyway.

But things have changed dramatically in recent years. The surprise re-discovery of Mariya Takeuchi’s 1984 single “Plastic Love” by Youtubers three decades later in 2017 made the song synonymous with Japanese pop for legions of listeners abroad. The song grew so popular that fans began creating parodies and mash-ups, my favorite being “Never Gonna Give You Plastic Love,” which blends in the vocals of Eighties megastar Rick Astley. (That photo of “Rick Takeuchi” makes me laugh every time.) It’s absolutely fine for new listeners to define J-pop in their own ways, but this surprise popularity made me start thinking about what J-pop originally meant to me. So I’m turning the clock back to the 1980s to find an answer. Put on your Walkman headphones and legwarmers and join me!

There are many varieties of Japanese popular music. There’s enka, which is like Japanese blues, melancholic and filled with vibrato, the hits of the Boomer generation. And there’s kayōkyoku, a slippery-to-define genre influenced by foreign pop standards. Kyu Sakamoto’s global hit “Sukiyaki” is probably the most famous of this genre. Some call kayōkyoku the ancestor of J-pop, but in common speech Japanese use kayōkyoku to refer to older pop songs that aren’t J-pop.

The dividing line between kayōkyoku or J-pop, I think, is television. More specifically, whether you heard the songs on TV, as opposed to just the radio. And when you talk about television, you can’t forget that the 80s was a golden era for another genre of Japanese music: the idol singer business. I say “business” because idols were presented to the public less as artists than as packaged fantasies. The genre hinged more on promoting a sense of closeness between idols and fans than it did musical ability.

Normally, I think, consumers buy albums because they like the music. It’s a quid pro quo kind of thing. But fans of idols didn’t pay for the music so much; it was more like showing support, or even paying tribute. Parasocial relationships are the core of the idol business. Idols weren’t independent artists; they were created and managed by talent agencies. And the more powerful the agency, the more the idol’s songs would get onto television. The notorious Johnny & Associates is a prime example: their brand of cute young boys was a nonstop presence on TV shows in the Eighties and Nineties. While idol music is its own thing, I think the idols of my youth have more in common with kayōkyoku standard-singers than they do with J-pop.

So what is J-pop? To me, it’s the music of independent singer-songwriters or bands. You had to have actual musical talent to make it in J-pop. Because they focused on the music, they weren’t always “TV-ready,” and didn’t appear on screen nearly as much as their idol contemporaries. As a result, if you wanted to listen to J-pop, you’d have to seek it out, catching a new song on the radio, getting recommendations from friends, or hearing a song by chance from a commercial on TV. During the Eighties and Nineties, commercials were one of the primary marketing tools for talented artists. For instance, many people first heard Mariya Takeuchi’s “Mysterious Peach Pie” as the backing track for a Shiseido lipstick ad.

Here’s another famous commercial from 1992, for the saké brand Gekkeikan. Hiroyuki Sanada saunters stylishly through a stylized and idealized Japan, to a soothing J-pop track by Anzen Chitai (“Safety Zone”) called “Anokoroe” (Here’s to those days). I really miss Japanese commercials from the 80s and early 90s! The best were more like dramas, subtle and artistic, selling the “stories” of the products rather than the products themselves. (If you can’t play the video below, here is a link.)

Mariya Takeuchi, on the other hand, I can’t ever recall having seen on TV. Many years later, I learned that this was deliberate: she was being groomed to be an idol after “Mysterious Peach Pie” hit, but refused and went independent, which she’s been ever since. So to me, Mariya Takeuchi isn’t an idol, but a J-pop star, because she writes and sings her own songs.

So that’s J-pop in a broad sense. But of course, for aficionados, the distinctions ran deeper. When it comes to Eighties J-pop, there are two key words: “city” and “beach.” Nearly every hit song of the era has one or both of these themes. And, how do you get to the ocean from the city? By driving. This is why so many J-pop hits have lyrics relating to cars. Drive me down the highway at night, sings Takeuchi in “Plastic Love,” the mysterious glimmer of halogen light. In fact, you could practically call J-pop the theme music of the Tokyo highway system. Driving to the beach – and not just any beach, but Shonan Beach in Kanagawa – was about the hippest thing a young Japanese could aspire to back then. And the soundtrack was the subgenre of J-pop we call City Pop.

It wasn’t the cars that enchanted me about City Pop, because I was too young to drive. It was the vibe, hip and urban, which, as a young Tokyoite, made me feel sophisticated and worldly. Writing it all out like this is making me really nostalgic for the J-Pop of my youth, so I’ve picked a handful of songs that I loved from this era, each one of which I learned about from one of the ways I mentioned above.

First is Toshiki Kadomatsu, who was one of my favorites back then. This is “Tokyo Tower” from 1985, which I first heard on the radio. If you were driving through Tokyo at night, this song was an absolute must.

Next is Toshiyuki Osawa, whose “Soshite boku wa toho ni kureru” (And I’m at a loss) came out in 1984. I heard this song from a Cup Noodle commercial! It grew on me, and so I added the track to my mixtapes.

Yasuyuki Okamura 1988 hit “Daisuki” (I love you) was used in a Honda commercial. But I found out about it through the schoolgirl whisper network. The fashions and the look of that video is so Eighties.

When I was in junior and high school, I listened to J-pop songs a lot. Mainly because I had noticed they told little stories, almost like books. Each song had its own protagonist, and listening made me feel like I was parachuting into the middle of these exciting personal dramas. I’d bask in the joy, excitement, or melancholy together with them as I listened along. It was like “watching” dramas with my ears, while the visuals unfolded inside of my head.

Mariya Takeuchi’s songs told stories, too. But I always treated her a little differently from the other J-pop artists. They were artists, but she felt like the big sister I’d wanted so bad that I’d even asked Santa for one as a very little girl. And Takeuchi sang about down to earth, everyday sorts of situations that anyone could easily relate to. This made her music feel like conversations with an imaginary big sister. To me, tracks like “Plastic Love” or “Eki” felt less like songs than heart-to-heart talks, where I could learn about what adult life was really like.

“Genki wo dashite” (Cheer up), from 1988, was one that really captured this sensation the most for me. It was a song about cheering up a heartbroken girl. I wasn’t heartbroken, myself, but the lyrics spoke to me nonetheless. Life isn’t as bad you think, went one line. Opportunity knocks again and again, went another. And you can always start over. I think those sorts of sentiments have become part of my worldview, even long after I grew up and left J-pop behind.

All of which brings us back to Takeuchi’s latest release, Precious Days. When I was a schoolgirl, I often listened to her music while I was doing my homework. So I did the same this time around, playing it while I did homework from my kimono class (this module is about how to sew kimono for ourselves.) As I listened, I picked up on familiar old themes as though by instinct. So my imaginary big sister is back, so to speak. I’m a grown woman now, of course, but I’m still looking for answers – that’s just how life is. Living vicariously through Takeuchi’s lyrics, I felt like my old big sister was back, encouraging me to “Brighten up your day!” (as the first track is titled.)

You can’t change the world But you can light up someone’s life Brighten up your day! Believe in yourself a little more Lighten up your heart! Start every day with a smile

“Everyday is a precious day,” writes Takeuchi in the liner notes of Precious Days. “It’s easy to think daily life is ‘ordinary,’ but I’ve started to realize that in a world filled with hardships, the ordinary is actually a miracle.”

I bought this album filled with nostalgia for the old days, but I ended up finding the words I needed to take me into the future. I recently read that there’s a trend in American publishing right now for “healing fiction” from Japan. Maybe Takeuchi is the healing music the world needs right now?

*Runs to Spotify to compile a playlist of everything you mentioned here in hopes I can find more clearly enunciated Japanese lyrics that are also groovy to listen to because right now I still only have Asako Toki on repeat*

Thanks for another great dive Hiroko!

Im def gonna have to dig into Takeushi now. As for someone who just fell down a rabithole of city pop this year and keen on getting them on vinyl, this was an insightful read.