Sightseeing with the Dead

Visiting graves can broaden horizons

June is, traditionally, rainy season in Tokyo. Traditionally, the temperature should drop, a brief respite before the punishing summer heat descends upon the city. But not this year, and certainly not this day. There wasn’t a cloud in the sky as I walked along a road in suburban Tokyo. I carried a parasol to create a little shade from the sun shining above, but nothing could stave off the heat radiating up from the pavement beneath my feet. What am I doing? I thought to myself as I trudged ahead, my body feeling as though it were shimmering with the heat-haze. I have a perfectly comfortable air-conditioned home. But I pressed on, because if I missed this opportunity, it would be another year before I got another chance to see the person I wanted to see. His name was Osamu Dazai. His vocation was writer. His address, my destination, was a graveyard in the suburbs of Tokyo.

Dazai wouldn’t be moving anytime soon, but this was a special day: June 19th, the anniversary of his passing away in 1948. That it was still being commemorated some eighty years later was a testament to how celebrated of an author he was in life. Actually, June 19th wasn’t the exact date of his death. He famously committed suicide by jumping into a canal with one of his lovers, but their bodies were found a week later on June 19th, still bound at the waist by a red rope. It was, coincidentally, also his birthday.

The deaths of famous folks are often memorialized with special titles, rather than calling them by name. Dazai’s is Oto-ki. It was coined by a novelist friend as a nod to Dazai’s last story, Oto (Cherry), and the fact that cherries were one of Dazai’s favorite foods. I learned this after stumbling across the information in a Japanese-language sightseeing pamphlet, which also mentioned that fans from all over Japan gathered to leave cherries on Dazai’s grave that day.

I wouldn’t exactly call myself a Dazai fan. I first became interested in his work after learning of his unexpected popularity among American anime fans – more on that in a bit – then read his acclaimed quasi-memoir No Longer Human. It’s dark stuff. But I respected it. And for some reason, I felt myself wanting to check out his grave on the anniversary of his death. He’s one of those writers who feels defined by death, both in the way he lived and in the way he passed. Somehow, a visit felt fitting.

Visiting graves is part of the fabric of life for Japanese. We often visit the graves of our relatives as a family, sweeping up and cleaning, offering incense and flowers, sometimes leaving an old favorite of the departed from when they were alive – some food, a bottle of sake, what have you. Although these visits are commonly conducted during specific holiday periods, such as ohigan in spring and fall, or obon in summer, it isn’t at all odd to visit outside of these times, either. There aren’t any strict rules; we go whenever we feel the urge, in the spirit of paying a visit to a relative. The only difference is that they aren’t visible anymore. When I visit my family’s graves, I talk. I like to tell them how things are going, ask them to say hi to other relatives or mutual acquaintances who’ve passed over to the other side. I know it’s a one way conversation, but it makes me feel better, especially when I’m missing them the most.

I’m not related to Dazai in any way. And as I said I’m not some kind of superfan. But my visit wouldn’t have surprised many Japanese anyway, because there’s another fashion of visiting graves here, not for mourning or remembrance, but simply for fun. This kind of visit is historically called sotai (掃苔), written with characters that literally mean “cleaning up moss.” Today, aficionados are better known as haka-mairaa (墓マイラー), from “haka-mairi,” or grave-visit, extended into a kind of verb, tongue in cheek. Haka-mairaa visit graves to celebrate the legacy or works of famous people (and the occasional celebrity animal, like Hachiko, whose statue sits in Shibuya but whose grave can be found on the grounds of a certain Tokyo graveyard.) It’s a way to show respect and gratitude.

Some haka-mairaa visit whenever they happen to be near an interesting grave. Others have turned the practice into a hobby, even a lifestyle. The literary researcher Kajipon Marco Zangetsu has visited more than 2,500 people’s graves in a hundred and one countries during the last thirty years! He’s literally crisscrossed the globe, visiting the Antarctic to pay respects to explorer Robert Scott, then the Arctic Circle for Roald Amundsen. He also journeyed to the distant Polynesian island of Hiva Oa to visit the grave of artist Paul Gauguin, among many other grave-visiting journeys. In an interview, Zangetsu describes a rough childhood, being raised by an alcoholic father. He says that literature, music, and paintings helped him survive his hardships. As he grew up, he came to see those artists who inspired him as benefactors. And so he decided to show his gratitude by visiting their final resting spots, first in Japan, then all over the world.

I’ve never considered myself a haka-mairaa (in fact, I only just learned the term while writing this newsletter!) But I understand where their feelings are coming from. I visit graves of people outside of my family from time to time too. For example, when Matt and I were writing Ninja Attack! I visited the grave of famed ninja master Hattori Hanzo to show my gratitude. Similarly, when we were writing its sequel Yurei Attack! we went to the grave of Lady Oiwa, star of Tokyo’s scariest ghost story, to ask her permission. (This is common practice in the kabuki world, too, whenever they put on a production of Yotsuya Kaidan.) And when we published Japandemonium Illustrated, we brought a bouquet of flowers to artist Toriyama Sekien’s grave, so that the three of us could celebrate his work coming out in English for the first time.

Dead people are invisible, because they’re no longer with us, physically. But as anyone who has lost someone close knows, they linger in other ways. And so I don’t see the dead’s invisibility as a reason or excuse to ignore them, even if they weren’t personally close to me. I didn’t know Hattori Hanzo or Lady Oiwa or Toriyama Sekien – they died centuries before I was born. But I (and my husband) wanted to pay our respects, because it felt like courtesy, manners, and simply the right thing to do. Their legacies and memories remain, nourishing generations of people who came after them, and will come after us, I suspect.

It’s fun to take a personal moment with such stars of the cultural scene. Plus, it’s an excuse to learn more about them. In Sekien’s case we didn’t just visit his grave; we went to the National Diet Library, dug up some very old maps, and pinpointed the location of his house/studio back in the 1770s. Then we used Google Maps to navigate there. Unsurprisingly, a brand-new modern home stood there, and I would bet you its occupants have no clue about the historic land upon which they’re now going about their lives. But it was exciting to stand where the artist who’d made the book that inspired us did his work, 250 years back. On our way back home, we stopped by an old little Japanese restaurant in the neighborhood. We ordered food for two, but I asked for water for three. It made it feel as though Sekien was sitting with us. When you open your heart like this, you realize that the people who passed away may not really be so far away from us after all.

Fans visiting to Osamu Dazai’s grave, especially on his death anniversary of cherry, is very much similar to that.

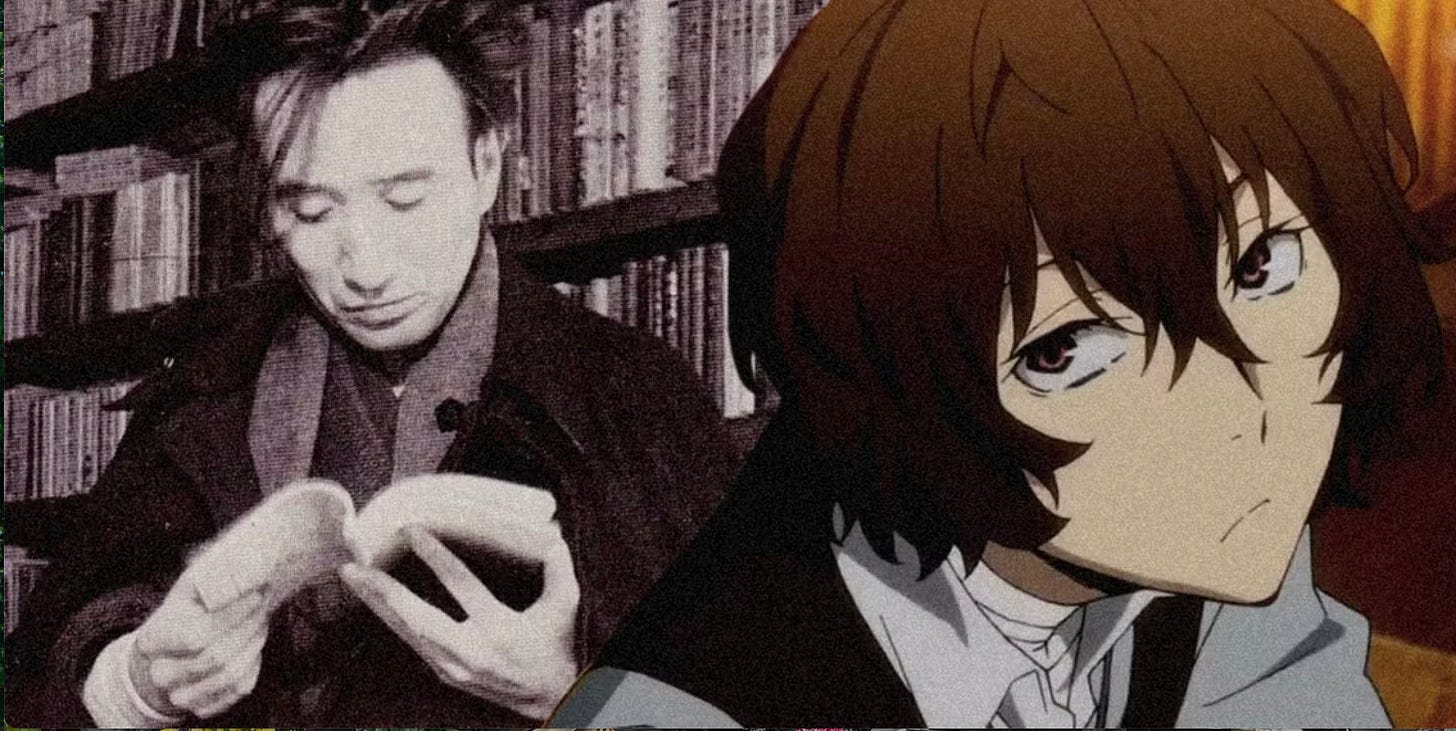

Osamu Dazai’s career spans the years leading up to and just after World War II. His most popular works are 1947’s Shayo (“The Setting Sun”), and the 1948 novel Ningen Shikkaku (which has been published in translation under a variety of names, most famously No Longer Human.) Shinchosha, his Japanese publisher, has put out 6.5 million copies of Ningen Shikkaku in Japan alone. But these days Dazai’s fame is not limited to the literary world, or even to Japan. The dour author was reinterpreted as a handsome young bishonen (beautiful boy) character in a manga series called Bungo Stray Dogs, which became an anime that was translated and released abroad in 2023. Dazai proved one of the most popular characters. At the peak of the show’s popularity, the hashtag “#dazaiosamu” racked up over 1.5 billion views on TikTok, and made an old English translation of No Longer Human a surprise bestseller. This sparked even more interest, and now Penguin Random House is putting out a new translation of the classic – the fourth! – in 2026.

The graveyard where Dazai now rested was inside of a Buddhist temple. Passing through the tile-covered temple gate, I found myself at the tail end of a line of well-wishers. They spanned the generations and demographics, a whole variety of people, old, young, middle age, male and female, all of us heading in the same direction. Many carried offerings in their hands: incense, cherries. By the time I made it to Dazai’s plot, there were maybe fifteen people hovering around his grave. Some watched quietly; others whispered conversations about the author in low voices so as not to disturb the others. It felt like an ad-hoc outdoor literary salon.

Dazai’s plot is arranged with a patch of open space about a meter square in front of the gravestone. On that day it was piled with colorful offerings, making it pop out against the gray background of the surrounding stones. Packs of cherries, flowers, beer, sake, whiskey, Pocari Sweat sports drinks (hey, it was hot out there), books, and more filled the space. Among them, I noticed more than a few bottles with a distinctive panda design. I knew exactly what they were – bottles of MSG, sold in supermarkets. Out of curiosity, I asked the man next to me, an older gentleman in a straw hat, what it meant. “Dazai loved MSG,” he said. Then he asked, “Are you a fan? Go ahead, stick a cherry into his name!”

I’d heard about the custom. Nobody knows when and who started it, but fans have been fitting cherries into the characters inscribed in Dazai’s tombstone. Presumably, they meant this as an offering, so that he might enjoy his favorite fruit in the great beyond. But I demurred. I hadn’t brought any cherries, for one thing, and even if I had, I wouldn’t have wanted to risk stepping on any of the pile of gifts left for Dazai. As I turned to depart, a teen-age schoolgirl still in her uniform passed me, carrying a small bouquet of yellow flowers. She reminded me of the illustration on the cover of Dazai’s novel Joseito (“Schoolgirl”). Is she a fan of the novel, I wondered? Or of the manga? It didn’t really matter; she was showing her respects along with everyone else. And now it was time for me to go, because I could see a new crowd of people moving in behind the girl.

Across from Dazai’s plot stood the grave of another classic novelist: Ogai Mori. He was a titan of the prewar literary scene, too, but nobody seemed to be paying him any attention on this day. I felt kind of bad, so I made a point of stopping and pressing my palms together in front of his grave before I left. Then I noticed something – a few cherries and a bottle of water. It seems someone had had the same thought as I did. Now Mori had some cherries to share with Dazai.

Osamu Dazai lived a life of despair, a despair reflected in his work. He was an addict, an alcoholic, and attempted suicide several times before finally succumbing in the end. I really wonder what he would think, what he would feel, if he could see all of these fans gathering at his grave today, paying their respects, showing their gratitude for the painful truths he expressed in his work, at terrible personal cost.

As I walked back home, I reflected on the fact that graveyards aren’t necessarily seen as dark or sad places in Japan. It’s true that it is extremely painful to lose someone. It’s easy to think that death is the end of everything. But one of the things I love about the Japanese worldview is that it helps us remember that death might not be the end we think it is. When we remember those we’ve lost, we also remember that they are and always will be there for us.

I wrote a book about my experiences and adventures exploring Japan’s spirituality. It’s called Eight Million Ways to Happiness, and is due out in December of 2025. You can pre-order it here!

Yet another thoughtfully written story of an aspect of human experience set in Japan. My real hero and a kind of senpai is YOSHIDA Shōin (1830-1859) as I am sure I have mentioned before. Many times I visited his grave in Hagi - and twice in Setagaya-ku in Tōkyō. And equally, many times, the grave of Mori Ogai (Rintarō) in his hometown of Tsuwano at the very southwestern part of Shimane-ken - just a tunnel length from north-eastern Yamaguchi-ken. And it's not only in Japan that I so indulged over the years - including in Matsuyama-city of TAKASUKA Jo (Isaburō) the pioneer rice-grower of Australia in the early 20th century - but also in England that of Pocahontas. Of war cemeteries - in Japan (Hodo-ga-ya-ku - Gontazaka BCOF cemeteries) on New Caledonia, in PNG - at Gallipoli in Turkey - etc etc - paying my respects - but also every time I visit my mother - now 95 and living some 300 km north of me - every six to eight weeks - calling in some 70 km south of her - to greet my father (and, yes, to commune with him, too) who died in a car accident in 1951 when I was just turned two) exactly 74 years ago to-day. Or my ancestors' First Fleet arrival to these shores in January, 1788 - my great x 3 grand-parents - buried in the graveyard of one of Australia's most historic churches - St Matthew's (Anglican) of Windsor to the north-west from Sydney's centre. Of other literary figures here in Australia - Henry Lawson, Barbara Baynton - both at Waverley Cemetery overlooking the Pacific Ocean in Sydney's east and so on. I visited my great uncle's grave in Warner, southern Alberta from whose given names came my own - James Stewart. He passed away in September, 1947. I was born in Australia 20 months later plucking a James from an uncle and the Stewart from my father - both named by their Scottish mother to honour her only brother - in western Canada. One of Australia's most remarkable cemeteries is in Broome in north-western Western Australia. Over 900 Japanese pearl shell divers lie buried there - from the latter through into the mid-20th century - not only from suffering "the bends" [sensui-byō] but mostly from suddenly-arriving cyclones (typhoons/hurricanes) when the fleets were diving on reefs some great distances offshore. Noted Australian folksinger/songwriter Ted Egan (and a former Administrator of the Northern Territory) wrote a song about such deaths: "Sayonara, Nakamura" - you can google him/it. To follow up on a point from Kjeld - when my mother passes away we will sprinkle her ashes over the graves of my father and of her second husband's grave as well. My wife and I who have no living children will be donating our bodies to the Medical faculty of our local regional university - there will be no memorial marker. But our presence may - who knows how - be there - in the air - all around the world - where we have lived, stayed or visited...

Although graves use a lot of real estate, it calms the heart being able to visit one. You have described that beautifully in this essay. There are no graves for my parents and grandparents and it feels lonely…