Status symbol of the Shogun era

How kosode evolved from underwear into the power-wear of the aristocracy

Last time, I wrote about how well the 2024 Shōgun TV miniseries captured Japanese traditional culture in old times, especially with regards to fashions. As promised, now I’m going to do a deeper dive on the subject of women’s kimono. This time, there’s no way around a spoiler, but it’s at the end and I’ll mention it clearly ahead of time, so feel free to read up to that point.

English speakers tend to refer to all traditional Japanese women's wear as “kimono.” Strictly speaking, however, kimono simply means “things to wear” – literally, as the word is composed of two kanji 着物, “wear” and “things.” There are actually many styles within this very broad category. Kosode is one, and I was delighted to see them mentioned by name Shogun ep.6. (As an aside, I think it is great that they used the Japanese words for traditional concepts like this, rather than glossing over them with English that doesn’t fit.)

Kosode is written with the characters 小袖, which literally means “small sleeves.” (So are there “big sleeves?” I’ll get to that in a moment.) Originally, kosode were underwear. But over the years, they evolved into a form of outerwear, and became a mainstay for upper class women in the Sengoku Jidai, the Era of Warring States.

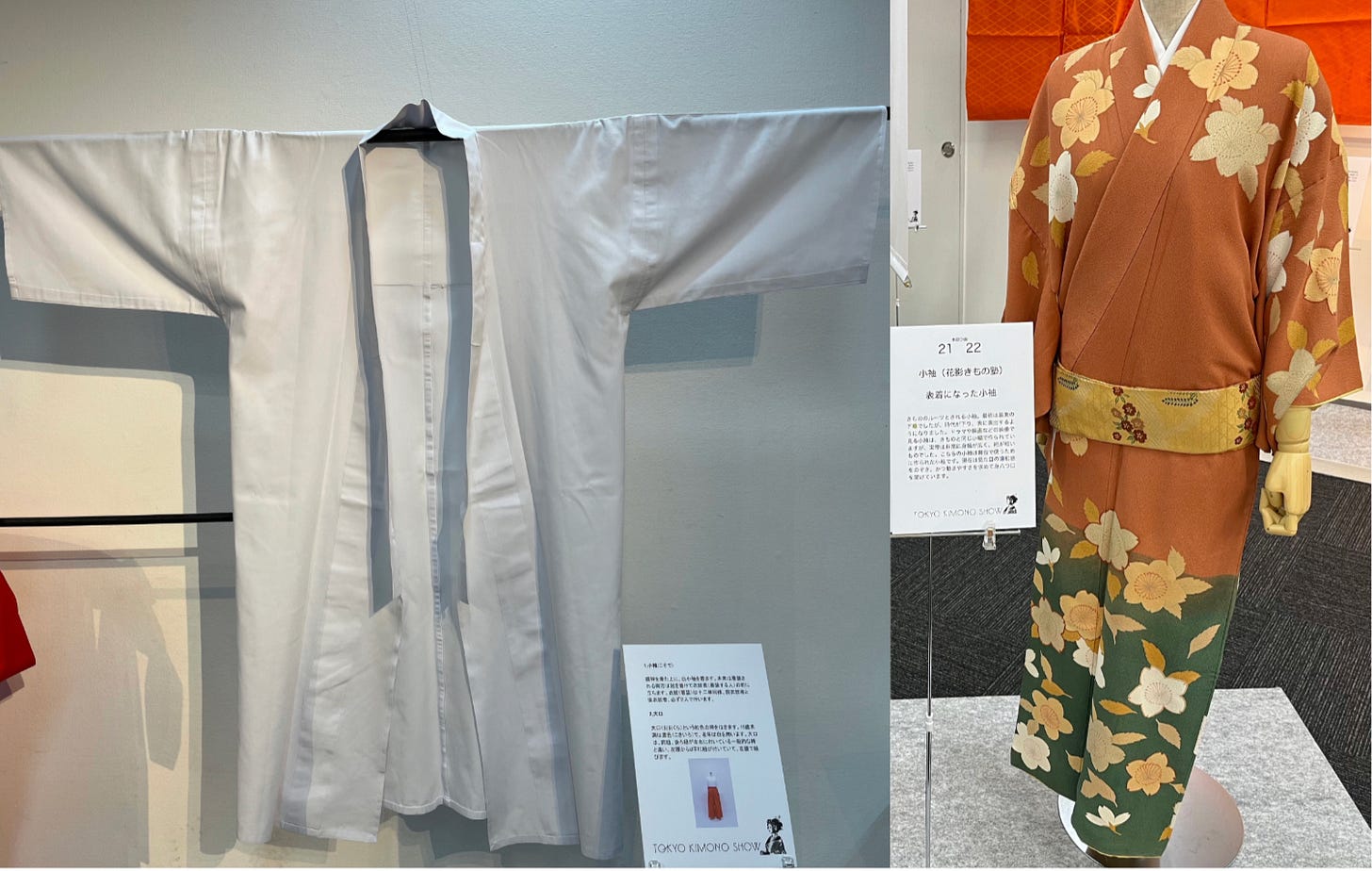

Below are photos from a kimono exhibition that I attended several months back. The white garment is a replica of the archaic form of a kosode, worn as underwear, from about a thousand years ago in the Heian era. Four or so centuries later in the Sengoku era, kosode had evolved into colorful outwear, still the same shoulder-to-ankle length, but intended to be worn over rather than under clothing. And they grew far more ornately decorated. This fancy wear is the style of kosode the brothel-keeper in ep.6 of Shōgun refers to.

Silk kimono were expensive, luxurious attire, only worn by the aristocracy prior to the Warring States era. Preparing a full kimono set (robe, obi belt, etc.) is time consuming, labor intensive, and requires a great deal of material – specifically, many thousands of silkworm cocoons. And that’s just the material. Assembling a kimono requires a wide variety of skill sets, from silkmaking to weaving to dyeing and, of course, tailoring.

Kosode were standard by the 1500s. But as I said, that wasn’t always the case. Turn back the clock three or more centuries to the Heian Era (794-1195) and you’d see women dressed very differently. Take a look at the pictures below. In the Heian era, aristocratic women pretty much stayed indoors their entire lives. They wore simple kosode as underwear, atop which they layered many gown-like kimono with big sleeves. These were not easy to move in. And the cost of making such an outfit would have been astronomical. As I wrote in an earlier newsletter, making a full kimono set – the obi belt, the nagajuban under-garment, the kimono itself, and assorted other necessities, requires nearly 9,000 cocoons. And that number is only for a modern one-layer kimono. I can’t imagine how many cocoons were required to make a full set of multilayered, extra-long aristocratic kimono!

Silk wear was for the upper crust. Common folk, such as farmers, wore kimono woven out of hemp, or undergarments worn as outerwear. In those cases they often added a thin silk apron, called a shibira-tatsumono, as a substitute for expensive kimono outer layers. The picture below shows how average women dressed in the Heian era. Look familiar? It’s a kosode.

Towards the end of the Heian period, the incessant corruption and power games among the nobility led to a great destabilization of society. The effete aristocrats found themselves outclassed by sturdy farmers who had begun arming themselves, learning horsemanship, and evolving into warriors – what would later be known as samurai. Over centuries, this change and instability led to the Warring States era, an era defined by gekokujo: an inverted social order, where the low reigned over the elite.

Kimono were another way of expressing social status. They were a highly visible “cue” to others that the wearer had wealth, authority and power. Kosode, formerly either underwear or humble clothes of the peasant class, grew more and more luxurious. So you can see kosode as a lens into the social politics of their era.

Even still, in Japan tradition dies hard. Kosode were still considered to a kind of undergarment, no matter how fancy. To differentiate themselves, higher-ranking women – such as Shōgun’s Mariko – wore long, gown-like kimono jackets, called uchikake. As I am writing this now, I realize that this represented a kind of fusion or hybrid between aristocrats and farmers, emerging as a new status symbol marking one as a family member of a high-ranking samurai.

Unlike the aristocratic ladies of the Heian era, the women of the Warring States took a more active role in the outside world. You may be wondering how they could function outdoors, wearing such long kimono. When they went out, they would either lift up the hems of their kimono by hand, or use a cord called a hiraguke-himo to tie up their kimono around their waist. You can actually see this cord, and the raised hems, in the screenshots below. (If you happen to study kimono today, this is the origin of the ohashori fold of modern kimono.)

SPOILER AHEAD!

Mariko’s hiraguke-himo actually plays a key role in episode 9. She uses it to bind her legs together in preparation for committing seppuku. This scene fascinated me, because I’d only read about this practice in books. It was seen as proper etiquette for a woman to maintain a dignified posture, even in death.

So in closing, kosode are an archaic form of kimono that aren’t worn today. Which means, in order to capture historical and cultural authenticity, the crew of Shōgun needed to create all of these period costumes from scratch! Kimono are still VERY expensive to make, even today. Looking at the kimono alone tells us just how huge of budget the series must have had!

After reading your previous article, I signed up for Disney+ and binge-watched Shogun. It was outstanding! This latest article definitely added another layer of understanding, so thank you for both.

Wonderful!