Summertime Sadness

Traditions nourish. But sometimes we have to change, like it or not.

Traditions are wonderful. I am in fact quite conservative when it comes to my nation’s traditions, because I see them not only as culture, but part of what connects us and holds us together as a society. But there can come a time when traditions bind. Almost by definition, traditions were made in the past — yet we’re moving inexorably into the future. Times change. And I realized when the times change so much that tradition becomes a hindrance, I need to give myself permission to change things up. If I’m feeling sad because of a tradition, what good is it doing me? But when I change, am I losing part of what makes Japan Japan, and me me?

These are big-picture philosophical questions, but I’ve been facing them in a very specific way lately. Japanese culture is incredibly weather-aware. The changing of the seasons is like the script for many things people love about Japan, from foods to traditional fashions. But the climate is changing, and with it, Japan is changing too.

Over the last few months, I’ve noticed that I tend to greet the day with a little sigh. It’s a bad habit, something that I know I need to stop doing, because a sigh is no way to begin a day. But every time I wake up and read the daily weather forecast in the newspaper, I can’t help it. Inevitably, there will be the icon for a manatsu-bi – “a mid-summer day.”

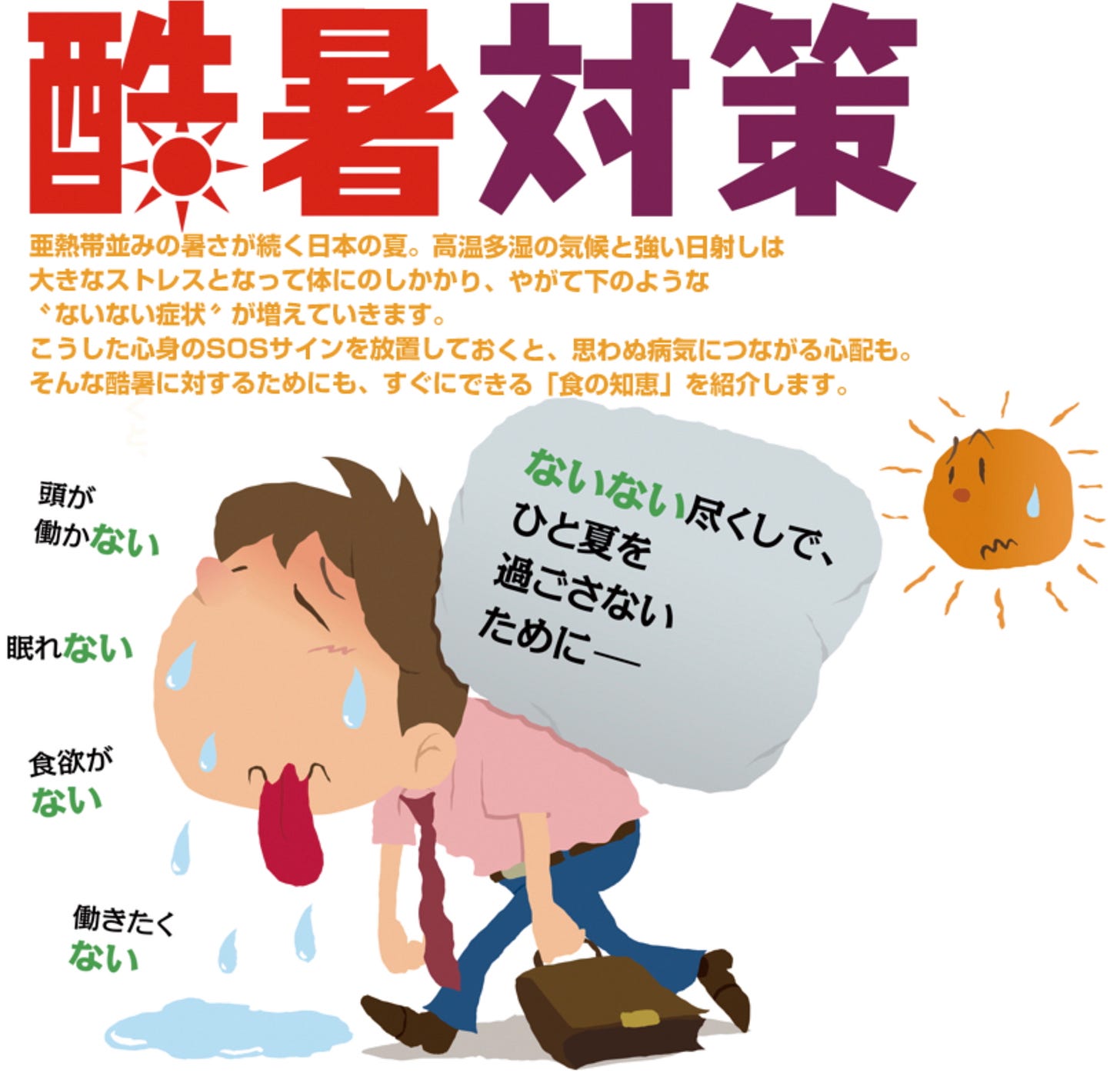

This sounds like a casual description, but is in fact a meteorological term coined by the Japan Meteorological Agency. It describes any day where the temperature exceeds thirty degrees Celsius, or 86°F. That’s to be expected in mid-summer. But the thing is, we are well into September, which is considered to be, or used to be, the beginning of fall, when things are supposed to be cooling down. And they aren’t. Just manatsu-bi after manatsu-bi, a seemingly endless summer.

I didn’t used to sigh over summer days. My memories of summer from childhood are pretty universally positive. The morning glories I’d plant with my mother in the spring would bloom, colorfully signalling the start of the season. I’d often grab a net for catching bugs and tromp out to the forest in search of kabuto-mushi, shiny rhinoceros beetles in samurai-like armor, prized by kids. I’d usually fail and have to content myself watching tiny antlions, which made little conical holes in the sand, waiting to feast on unwary ants that tumbled in. And as summer neared its end the neighborhood would throw its bon-odori summer festival. The sound of drums would resonate over the rooftops, and my mom would put me in a yukata and send me off to join the neighborhood kids dancing around the stage.

Back then, in the Seventies and Eighties, the average summer day in Tokyo averaged just 27°C, so a manatsu-bi of 30° could make the news. I remember, many years back, sitting at the kitchen table while my mother prepared supper, and the TV reported we’d be getting a heat spike the next day. Both of us stopped what we were doing and exchanged glances in surprise. The fact that we did, and that I even remember it so many years later, shows just how unusual a manatsu-bi was back then.

In fact, our home wasn’t even air conditioned at the time, save for my parents’ bedroom, and they almost never ran it. Neither was my school air conditioned. Most schools weren’t. We didn’t need it. If things got hot, even in mid-summer, all we had to do was open a few windows. Or run a fan, which I loved, because I could talk into it and enjoy hearing my voice change into a robot’s.

We had so many gentle ways of beating the heat. Eating cold somen noodles, or a slice of watermelon, or kakigoori shave-ice, or ice cream. My mother would give my younger sister and I a hundred yen coin each and we’d dash off to the local family-run cake shop, which also carried ice cream and popsicles. Our favorite was the “Jewel Box,” which was vanilla ice cream with chunks of fruit-flavored soft candies inside.

My absolute favorite thing to do on a summer day was taking a nap on my father’s side of the bed. It was next to a window with southern exposure, and the coverlet would get really warm in the afternoons. I’d curl up like a cat and fall asleep to the sound of the cicadas. I’d inevitably wake drenched in sweat, but I felt good. Maybe it was like a sauna. I’d shower off and have a nice cold glass of mugicha barley tea out of the fridge.

Summer felt precious to me as a child because it felt like a discrete period with a fairly specific beginning and end. But recently, that hasn’t been the case. It begins earlier, lasts longer, and gets hotter year after year. The gentle ways of making it through the heat don’t work so well anymore. Remarking to each other how unusual summer is has become altogether usual.

In 2007, the meteorologists debuted a new descriptor: mousho-bi, or “fiercely hot day,” used when the temperature exceeds 35°C, or 95°F. The mass media coined even more variations in the years after, including kokusho, “extreme heat” (40°F or higher) and the distressing-sounding saigai-kyu, or “disaster-level” heat. In 2024, the government started pushing heatstroke alerts to phones whenever the temperature hit that thirty-three degree mark.

You’d think a longer summer might mean more chances to have summer fun. But not when it’s this hot. Unpleasant heat forces me to stay indoors and run air conditioning. This makes ice creams and cold noodles a lot less fun to eat. I stopped making cold barley tea because I’d rather have hot coffee. Katori-senko incense is too smoky to burn in a closed room. I can’t even imagine re-creating those summer naps on my dad’s bed; I’d get heat stroke now. This sounds a little like “first-world problems,” but the heat really can be dangerous, and there’s a slow-build psychological impact to letting go of so many things I once took for granted. There’s a comfort in the old ways, and distress when you have to let them go.

Sometimes, though, you simply have to adapt. Let me give you an example.

Yukata are Japanese traditional casual clothes. The word is written 浴衣, which means “bathing wear,” like a robe, or even pajamas, because Japanese traditionally bathe in the evening. That is why many ryokan (and business hotels) provide guests yukata all year round – they’re for relaxing in.

There are many customs when it comes to traditional fashions in Japan, and yukata are no exception. The biggest custom is that they are “season sensitive.” Yukata are supposed to be worn outdoors only in summer, July and August, and then mainly in the evenings. You might get away with wearing one at the end of June, but September? Never – because that’s typically fall, unless there’s some very special exception, like an early-fall festival. Otherwise wearing a yukata in September would feel like wearing shorts in winter or a snow parka in summer. Just out of season.

But things have changed. I remember a big turning point for me, in midsummer about three years back, when the temperature shot up even higher than usual for July and August. My iPhone was chiming with heat alerts almost every day. I’d studied kimono during pandemic, and even got a teaching certification, so I’d made a habit of wearing a kimono once a week. But it was getting a lot harder to do this in the summer. There are lighter summer weight kimono, but they’re still heavier than a yukata. And they’re expensive, being made of silk. Not only were they getting uncomfortably hot, but I was worrying about ruining them with sweat, too.

So I decided to try wearing a yukata instead. This might seem like a reasonable compromise, but you have to remember, I’d been traditionally trained, and was now going up against literal centuries of common sense about seasonal fashions. A yukata in the daytime felt totally wrong to me. I resigned myself to not wearing traditional clothing until it cooled, whenever that might be.

September came. The temperature was still high but had cooled enough to make walking outdoors more bearable. There was just one problem. Now it was September, and in September, yukata are traditionally out. I tried it once, but almost immediately turned around because it felt so wrong. And this made me really sad.

But as I walked back home, I noticed women walking by in shorts and flip flops and all sorts of summer gear, even though it was theoretically fall. They’d adapted to the weather because they were wearing Western clothes, which had a lot fewer rules associated with them. Why could they enjoy themselves, and I couldn’t?

No reason at all.

So I had an epiphany.

I made the decision to let go of tradition, at least when it came to yukata in September This might seem a small thing. But I think it reflects something a lot bigger. We live in a particularly dynamic time, when we’re faced with changes of all sorts, in all spheres of life. It’s easy to get hung up on the past. I won’t lie: it hurt to have to break tradition in this way. I’ve always seen wearing kimono and yukata in traditional ways as a connection to the past, of my family, of my people.

But I realized that making changes, in a thoughtful and respectful way, isn’t a repudiation of tradition or culture. It’s a tool for surviving. If you ask me, you don’t need anyone’s permission to change the way you do things. But that doesn’t mean you won’ feel a certain degree of resistance. Overcoming that takes a sort of courage, which I say not to pat myself on the back but to acknowledge that change doesn’t come easily.

I still love my country’s traditional fashion calendar, and want to follow it when I can — if things improve on the climate-change front I’d happily go back to the way things were. But I’d rather change a little than give it up altogether. Changing things up when we have to is a tool for making ourselves comfortable and happy in the here and now. I’m not saying it should be done lightly. But when we have to, we shouldn’t beat ourselves up about it. These days, we need all the comfort and happiness we can get.

I wrote a book about my experiences and adventures exploring Japan’s spirituality. It’s called Eight Million Ways to Happiness, and is due out in December of 2025. You can pre-order it here!

I grew up in Japan in the 60’s and 70’s. Hot summers! But now with the extended summer months it really can wear you down. Now living in CA we get fairly erratic temperatures these days. This summer has been milder than some but now in September I’m using the AC for the first time.

We adapt. We have to.

I feel your nostalgia.

Thanks for sharing! The stories about your childhood are incredible to me, someone who’s only known a much much hotter Japan.

I have some kind of secondhand nostalgia for Japanese summer probably because of how many games and anime I grew up watching happened during summertime, the time for kids to imagine and have adventures.

But I mostly just stay inside mid July through mid September until the sun goes down, if I can help it.