The Shogun Code

How an American show lifts the curtain of Japanese culture

Speaking very broadly, linguists divide languages into “high context” and “low context” varieties. High context languages tend to rely heavily on shared cultural knowledge; low context ones less so. Japanese is considered high context, which means that fluency in the language from a linguistic standpoint isn’t necessarily enough to make one “fluent” in social communication. There are many unstated assumptions about manners and etiquitte in Japan. You may agree or disagree with them, but if you don’t understand them, you will have a hard time conveying your intentions to others.

There are some great examples of this in the 2024 reboot of the “Shogun” miniseries. And don’t worry – no spoilers!

As a Japanese person, I’ve been fascinated by how well the series nails period language, style, and mannerisms. As Hiroyuki Sanada, who plays Lord Toranaga in the series, put it in an interview with the Asahi Shimbun newspaper last week, “it’s still considered rare to hire Japanese actors for Japanese roles in Hollywood.”

But thanks in large part to Sanada’s efforts (not to mention a whole team of Japanese producers, translators, and fixers behind the scenes), “Shogun” bucks the trend. It is filled with cultural symbolism and subtleties that are essential to Japanese communication, even today. There were three moments in particular that struck me as the sorts of things that capture this culture of nonverbal communication. Some only lasted a few seconds, and I suspect a lot of foreign viewers may have missed them. They might seem trivial at first glance, but if you look closely they do a great job of expressing some of the nonverbal cues of a high context culture.

The first example involves a cushion. In this scene from episode 7, the brothel-owner Gin has been granted an audience with Lord Toranaga. His retinue sits directly on the floor, as they serve beneath him. But Gin has been given a cushion – a non-verbal cue instantly understandable to Japanese: she is not part of Toranaga’s “posse,” so to speak, and is a guest in this space.

Yet if you look closely, Gin isn’t sitting on the cushion, or not exactly. This is another non-verbal cue, from Gin to Toranaga: I may not be one of your retainers, but I look up to you, and humble myself in the way your retainers do. In fact, not sitting directly on a cushion offered by someone you see as “above” you, socially speaking, is still considered a social grace in Japan today.

But there’s more. Note how she sits, with one knee touching the cushion. This is another non-verbal cue that Toranaga would instantly interpret as a show of politeness. By putting part of her body on the cushion, she silently expresses that there isn’t some problem preventing her from using it. It accentuates her effort to humble herself before Toranaga. So as you can see, this simple cushion is doing a lot of heavy lifting as a tool of communication!

Here’s another fun example from the same episode. Toranaga welcomes his brother with a fancy meal. But not just any fancy meal. A tai red snapper and an ise-ebi rock lobster are prominently, even theatrically, displayed. Japanese food is known for the attention to detail regarding presentation, and this looks great, but there’s actual information being conveyed here, too.

Why snapper and lobster, and not, say, scallops and natto? With the fish, the answer can be found in its name: tai sounds like medetai, or luck and joy. Japanese culture is full of wordplay, where things whose names evoke positive words become associated with celebration, prosperity, and happiness. That makes red snapper an auspicious fish. The association remains today; we serve tai on special occasions, which is why Ebisu, one of the Seven Lucky Gods, carries them on every can of Yebisu Beer.

As for that lobster, the answer comes more from biology. Rock lobsters “wear” suits of strong armor. And their shedding to grow larger is seen as a symbol of advancement in life. In other words, this menu expresses Toranaga’s aspirations for his brother at this moment.

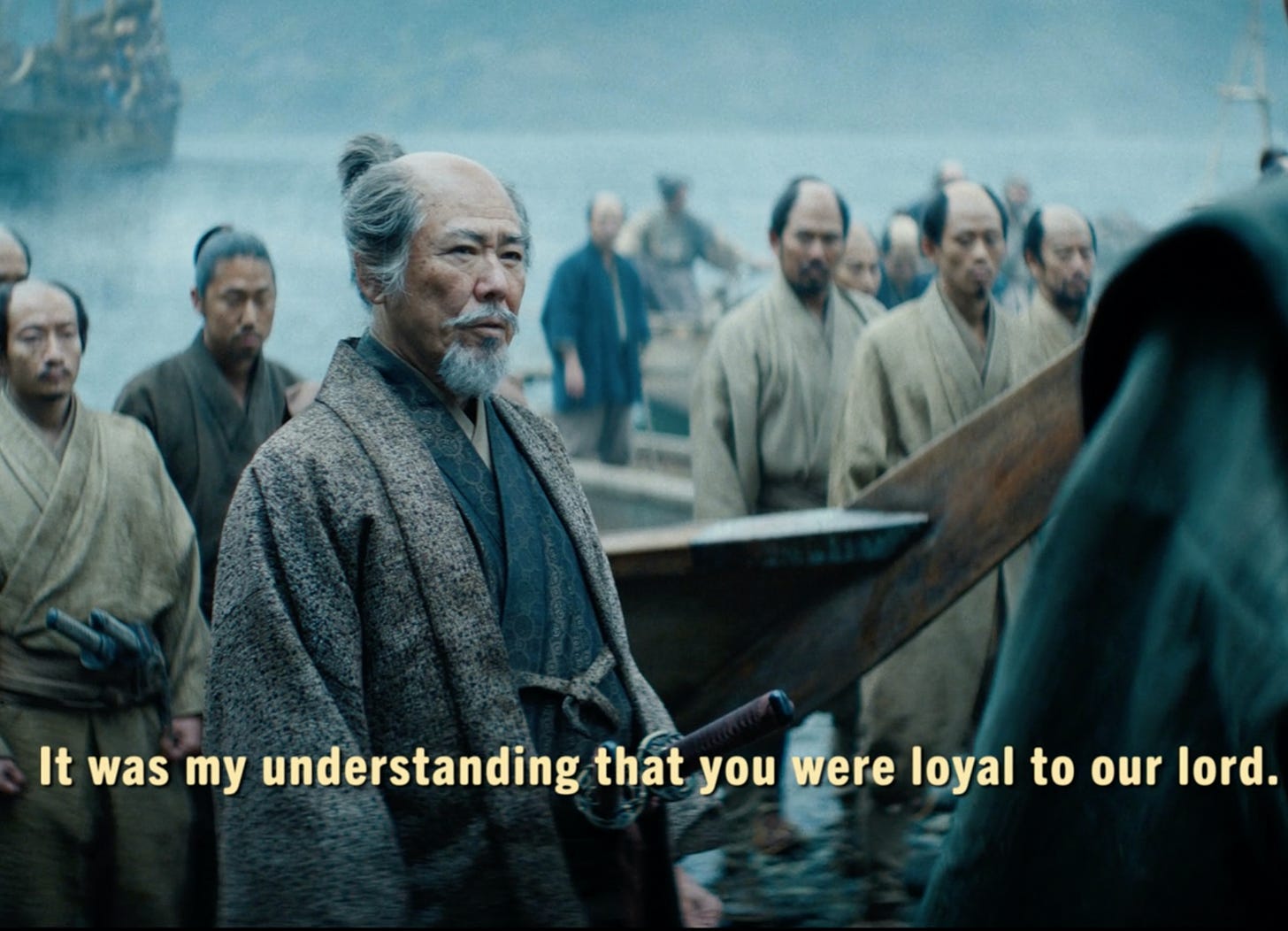

Finally, a moment from episode one. Hiromatsu, Toranaga's steely-eyed general, is in a discussion with another warlord. Their initial meeting is tense. At one point, Hiromatsu states cooly that “it was my understanding that you were loyal to our lord.” Then he subtly shifts the grip of his sword downward. The message is simple: be careful about what you say next, or I might draw this and strike you down. But Hiromatsu never breaks eye contact or even raises his voice. It’s another great example of a non-verbal cue.

I’ve seen Japanese katana used in so many Hollywood movies. Actors are often seen carrying them on their backs, or swishing them around casually, as if dancing or waving a magic wand. I’m no swordswoman, but these scenes always struck me as “off.” Swords are never treated lightly in Japan – they’re seen as divine tools made for a singular purpose: taking of life. There’s even a saying that “a good sword is one that has never been drawn.” It’s good to see an American production get it right. Hiromatsu radiates a “killer aura” without ever pulling his sword from its scabbard.

Sanada told the Asahi Shimbun that he hopes Shogun “helps establish a ‘new normal’ for portrayals of foreign culture in Hollywood,” not only for Japan, but everywhere. I hope so too!

While I look forward to watching this new TV drama in Japan, where I live, I thank you in advance for deciphering these 3 examples of non-verbal, high-context details.

The original novel by James Clavell has always been one of my favorite books, and it even played a role in my decision to begin to study Japanese more than 3 decades ago. I am especially curious about any cultural misappropriations and other anomalies from the book and miniseries.

Fascinating. Thank you, Hiroko!