Yoshiwara: Edo’s Virtual Reality

The hard truths behind the fantasy of Japan's “floating world”

The University Art Museum in Ueno held a special exhibition on the Yoshiwara last week. This was a rare opportunity to see a lot of art from Edo’s “pleasure quarters” in one place. The show is over, but I wanted to tell you about it, and show you some of the things I learned there, because it’s important – and surprisingly relevant to our modern times, as you’ll see if you read through to the end.

Yoshiwara was a famous, in fact the most famous, yūkaku. The word literally means “pleasure quarters,” and it was the officially-sanctioned red-light district of old Edo. The Tokugawa Shogunate approved its construction in 1617. The idea was to concentrate all of the city’s brothels into a single place, the better to keep the city, and its men in particular, under control. In effect, it was a sort of sexual theme-park for men, engineered by the authorities.

The Yoshiwara was a major operation. It occupied a swath of real estate on the edge of the city that was the size of two Tokyo Domes, and was home to several thousand women, who worked there around the clock. Patrons spent money, often large sums of it, to eat good food, drink saké, listen to music, and have sex with courtesans, who dressed up in opulent kimono and hair accessories, perfuming themselves with expensive incense.

The atmosphere was opulently festive. Fresh flowers and even entire trees were carted in for display on the main boulevard to suit the seasons. Parties ran day and night, but night never really fell there, for the moment darkness encroached it would be driven off with extra-large candles. Over the centuries, Yoshiwara evolved from a brothel into the city’s cultural epicenter, with its own unique slang, mannerisms, and fashions. In the premodern era, it was one of Edo’s most popular entertainments, right alongside Kabuki theaters.

Popular for men. For the women, it was something different. Working in the Yoshiwara wasn’t simply a job: it was their entire life, for the women of Yoshiwara were forbidden to leave. To them, it was a literal prison. The quarter was surrounded by high walls and a moat for good measure. There was only one entrance, strictly guarded so that none could escape. Working in the Yoshiwara wasn’t a choice. Many of its female inhabitants had been sold to one of its proprietors as children by human traffickers, who used famines, natural disasters, and other tragedies to target rural families who couldn’t afford to feed their children. And when those little girls came of age and inevitably became pregnant, their children would remain within the walls as well.

The women of the Yoshiwara weren’t simply sold into bondage – they were charged extortionate rates for the “privilege” of living and working there. Their living quarters, their clothes, their cosmetics and food – their owners charged all of it back to them starting from the moment they arrived. In essence, they began their lives saddled with debts that were nearly impossible to pay off.

The ukiyo-e prints of Edo represent some of Japan’s most iconic art. Hokusai’s Great Wave over Kanagawa is one, as is another favorite, the Princess Takiyasha conjuring a giant skeleton. But perhaps the most popular subjects of all were courtesans from the Yoshiwara. They were the idols of their era, portrayed as perfectly poised, stylishly coiffed, and fashionably dressed.

The word ukiyo-e is interesting. It is written with characters meaning “pictures of the floating world.” The floating conveys a sense of otherworldliness and detachment from the real world. It evokes hedonism. Ukiyo-e were a form of fashion photography centuries before the invention of the camera, filtering out all the ugliness of reality. Their women are inevitably healthy and young and willowy, their slender bodies covered in layers of opulent silk kimono, their heads adorned with expensive ornamental accessories.

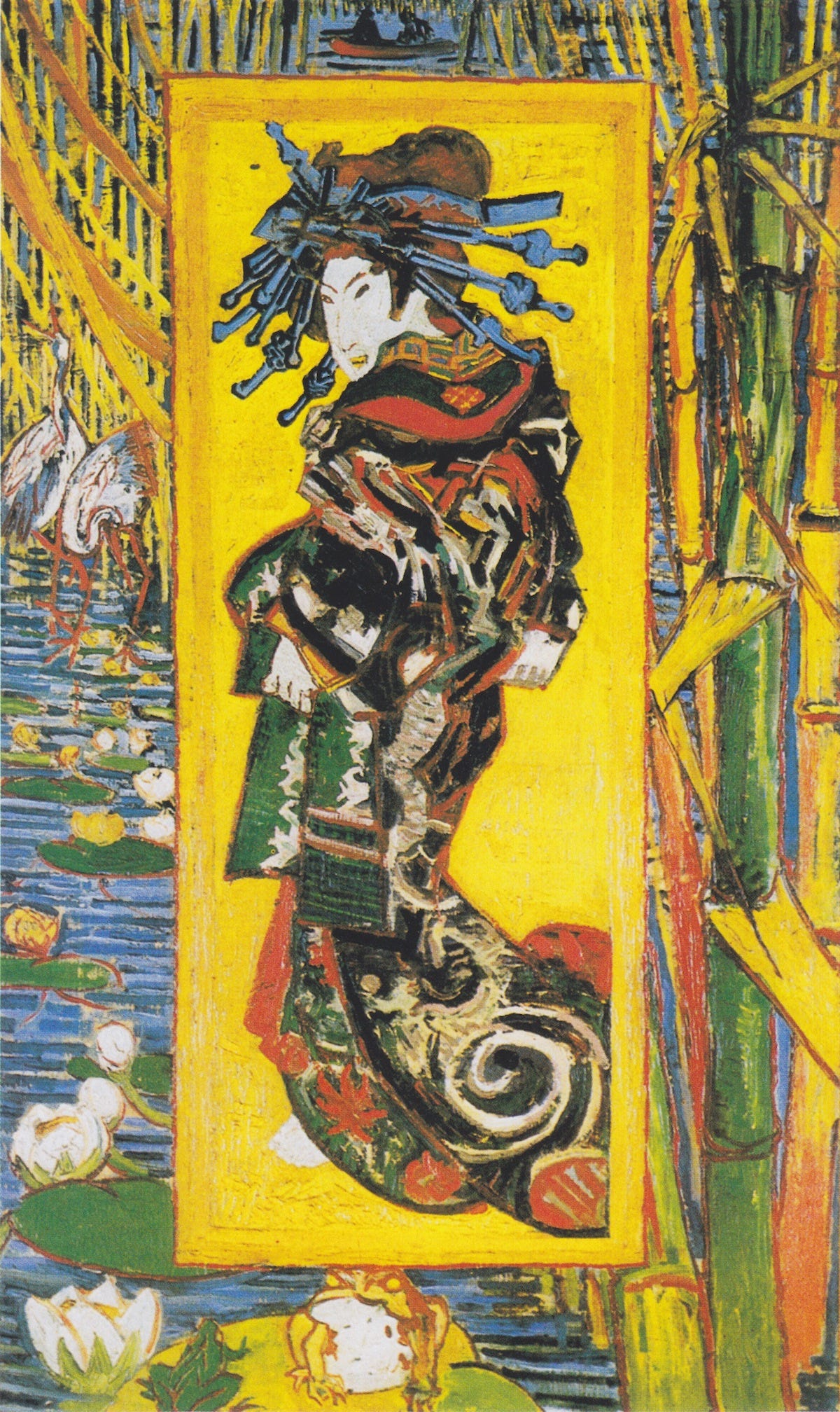

Artists curated what they saw in the red-light district to construct enchanting fantasies of pleasure and happiness. They were so good at it that they enchanted foreigners, such as the Impressionists who incorporated ukiyo-e styles in the late 19th century. They were so good at it that they even enchanted me. I found prints of Edo courtesans pretty, too, like an extravagant kimono fashion show, with Yoshiwara as the runway. That’s why I wanted to go see the exhibition in Ueno.

The museum put more than two hundred items on display: paintings large and small, folding screens, accessories, furniture, and more. A majority of the pieces were ukiyo-e prints, many by globally renowned artists (and Yoshiwara patrons) like Hokusai, Utamaro, and Hiroshige. In modern times, there is much more awareness of the suffering women endured within the walls of Yoshiwara. Because of this, exhibitions centering on it have become quite rare. The University Art Museum took great pains to contextualize its exhibition, declaring in a video presentation at the beginning of the show that “we not condone human trafficking in any way, shape, or form.” It was a hint that this wouldn’t be the usual celebration of beautiful courtesans.

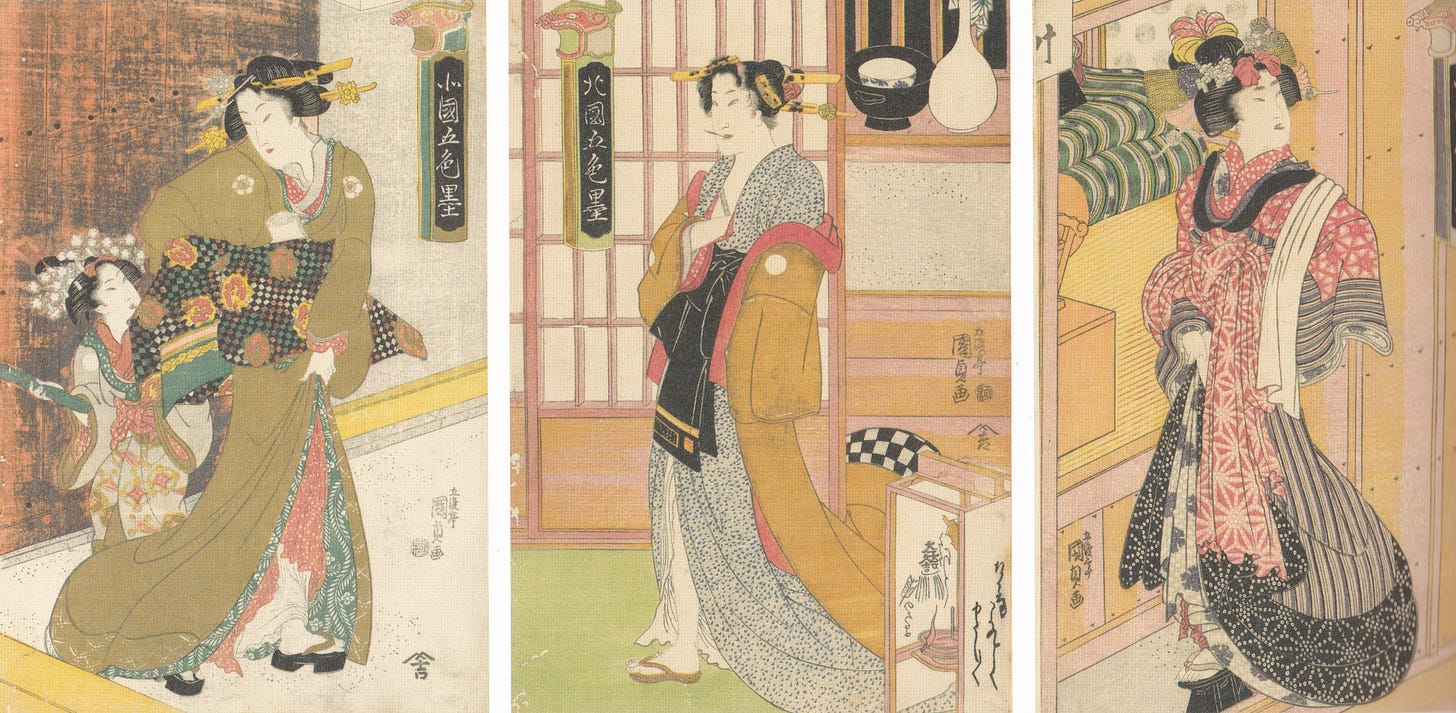

Women in ukiyo-e prints seem to have “secured” their bodies beneath multiple layers of kimono. But there was a subtle “kimono code” in the Yoshiwara, and if you know it, you can tell which of these women is signaling that they’re ready to take off their garments for a customer. Here is an example.

Kunisada Utagawa made this print of five women occupying different positions in Yoshiwara’s cloistered society. From top left, you can see a geisha, a kashi (low-ranking prostitute), and a kirimise (the lowest of the prostitutes). From bottom left, you can see the wife of the owner of a brothel alongside an oiran, the highest-ranking courtesan. Among them, only one sends a signal saying “no sex.” Can you tell which one? I’ll make it a little easier. The kashi and oiran’s kimono are already loose, their sensual messages obvious. So who is off limits?

The answer is the geisha. Look how she holds her under-kimono with her left hand, whereas the kirimise and even the wife are holding their kimono with their right. The holding of a kimono fold with the left hand was a Yoshiwara-specific cue that a woman is off limits. It’s due to the structure of a kimono, where the left collar is placed over the right. The kimono of the era were much longer than today’s. So when a courtesan walked, she had to hike it up. And due to the way a kimono is folded, if you do that with your right hand, you will “flash” what lies beneath.

Most ukiyo-e, being fantasies, are beautiful and celebratory. But I found one that stood out from the others, a triptych by Kunisada. It portrays a kirimise brothel, where the lowest ranking prostitutes worked in the worst part of Yoshiwara, in the houses alongside the moat. Art showcasing the lowest prostitutes is rare, for the consumers of prints wanted fantasy, not reality. For instance, there are a disproportionate number of ukiyo-e featuring oiran and tayū despite the fact these “superstars” of the quarter numbered only a tiny few – just one out of 2,312 courtesans in a 1691 survey.

The kirimise, on the other hand, were not stars. Kunisada’s prints show them in patchwork kimono that were probably even more tattered in real life. Their obi belts are made of thin fabric. Their hair accessories look as though they were grabbed at random, and the woman at far right’s hairstyle is much smaller than the others; she probably couldn’t afford a stylist and did it herself. Meanwhile, I can practically hear the woman at center shooing the others away as she sweeps up. At left, a woman pours boiling water into a bucket to disinfect clothes. Behind her, a woman pours a powdered drug of some kind into an open palm.

It reminds us how endemic poverty and sickness were in Yoshiwara, alongside malnutrition and sexually-transmitted diseases like syphilis. The average lifespan of a courtesan was just twenty-two. The vast majority were not considered worthy of proper funerals. Their kimono were stripped for use by other courtesans, and their naked bodies wrapped in straw mats and left at the entrance of a nearby Buddhist temple, for the monks to provide last rites. It was popularly known as Nagekomi-dera, “the throw-away temple,” and contains the remains of some 25,000 former quarter residents. It still stands today.

The Yoshiwara went through many iterations over the centuries. The restrictions on women leaving were lifted by governmental decree in 1872, as the nation slowly began to modernize. And the Yoshiwara remained in business until 1957, when the Japanese government banned prostitution legally, if not effectively. But the quarter had been in serious decline for many decades before that. Tellingly, I think, this slow fall paralleled the rise of a new technology: photography.

The exhibition ended with a series of photographs taken in the Yoshiwara. Their reality stands in sharp contrast to the fantasies of the ukiyo-e, almost like a wake-up call. These pictures were no fantasy; they revealed the truth of Yoshiwara in all of its unvarnished reality, their gray tones echoing the darkness of life for the women forced to labor there. This particular one wasn’t part of the display, but it’s no different from them. It was taken in the Yoshiwara in the late 19th century.

Even after the women were supposedly freed, the women remained in effective bondage, and the tragedies continued. In 1923, a fire caused by the Great Kanto Earthquake swept the quarter. The women tried to run, but the proprietors had locked the gate. Desperate to escape the flames, the women leapt into a pond inside the walls. About 500 suffocated or drowned in the panic. I can’t help but wonder if the girls in the photo were among them. Certainly girls just like them were.

The highlight of the exhibition was a massive painting by Utamaro, titled Yoshiwara no Hana, or “Cherry blossoms at Yoshiwara.” On loan from the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, it provided an impressive centerpiece: two meters by two and a half meters, like a window into the floating world as imagined by Japanese in times of old.

I went back to take another look after seeing the Kunisada tryptich and the photographs. I was more convinced than ever that the painting was a beautiful fantasy. But whose fantasy? There are no customers in the frame. None of the ladies hold their kimono with either right or left hands. There is no signalling here, just joy, the joy of women holding a party for themselves. The setting does not seem to be based on any specific real-world brothel, but rather a generic party space. I noticed azaleas beneath cherry trees in full bloom. Yet Azaleas are late bloomers, a month after the cherries. They’d never bloom together. That’s when I knew: this was a fantasy, pure and undiluted. This was the ukiyo given form. Perhaps it was Utamaro’s tribute to the women who’d given their lives to the quarter, given a chance at happiness at last.

The word ukiyo is written with the characters 浮世. It was coined in the Edo era from the homonym 憂世, which means “the world of grief and worry.” Ukiyo-e is a pun created by a woodblock prints publisher. This makes them two sides of the same coin: heaven and hell, pleasure and sadness, coexisting in art as they do in life.

That’s what gives ukiyo-e prints their pull today, I think. They’re a kind of virtual reality, constructed from wood and ink and paper instead of glass and plastic and silicon, but similar nonetheless. We try to put our best faces on our struggles too, in the way we curate our TikToks and social media feeds and all the rest. We show our triumphant faces to the world while hiding our darkness from it. The pictures of the floating world show us this filtering of reality is nothing new.

Thank you so much for these insights on the Floating World. What a horrible fate these girls and women had, and there's this whole elaborate fiction of off-limit geisha, fantastic kimono, perfect make-up and hair that was based on their very real suffering. So sad that, all over the world, women's fate and suffering seems to count very little, everybody seems to be much more interested in the fiction and the fantasy...

Thank you for your thoughtful article. I wish I could have seen the exhibit.

Every time I go to Tokyo I go to that “throw away” temple and leave something at the place where many of the urns for those girls are kept. I’m not the only one. People leave sake, hair clips, and the like.

If I remember correctly, a memorial area for the writer Nagai Kafu is just across from that small mausoleum. On some days you will find a man on a bench playing shakuhachi for the young women.

The former Yoshiwara district is walking distance from the Higuchi Ichiyō museum. Please please read her short story “Takekurabe” (or “Child’s Play” in some translations) to get closer to these women.

It took me a few trips over decades, but I eventually found the location of the Yoshiwara as well as the “throw-away temple” (still functioning, as you mention). The Yoshiwara street layout is the clue if you compare original and contemporary maps.

The area now (again?) features a lot of hostess clubs and soaplands. There are markers for the original main streets. There are no tourists. There are expensive, chauffeur-driven cars that cruise through.

One of the original Yoshiwara brothels (Kadoebi) is still operating, but there’s nothing glamorous at all. It’s a bit of an eye-opener, like your article.