I went to hell last week

...and had a great time!

I just got back from a trip to Toyama prefecture. My husband and I went there to climb Tateyama, a famed peak in the region. At 3003 meters, it was the tallest we’d summited. Getting up there took a lot of preparation and training. It also took us through hell.

I don’t mean this metaphorically. The photo at top is Jigoku-dani, literally “Hell valley,” which sits near the base of Tateyama. The trail up and back leads right past it.

Tateyama is absolutely beautiful, as you’ll see from the pictures below. Why would Japanese name a place in the middle of so much natural splendor “hell?” For one thing, Jigoku-dani is an active volcanic site, stained white and yellow by sulfur and other compounds, with bubbling natural cauldrons of water and fumaroles belching acrid steam into the air.

This sulfurous scene evokes jigoku, which is the word for the Japanese concept of hell. It differs from the Christian-influenced hell of the West, in that pretty much everyone is destined to wind up there after they die. The reason being that, in the braid of Japanese spirituality taken from Buddhism, none of us is without sin. We take lives to eat; we smash insects, whether deliberately or by accident. We argue and upset others in ways large and small. The definition of sin is entirely subjective, but I suspect there are few among us who don’t have something they regret having done in their lives. In this worldview, almost no one who has lived is truly free of sin.

Sin may be subjective, but according to Japanese folklore, the first person you’ll meet after dying and going to hell is an old woman who measures them very accurately. She sits at sai-no-kawara, the bank of the River Sanzu, which divides the realms of living and dead. When you meet her, she strips off your clothes and hangs them over a tree branch. The more it bends, the heavier your sins. She reports this to Lord Enma, the judge of jigoku, who will pronounce your sentence later.

The thing is, in Japanese spirituality, jigoku isn’t the end of the road. Everyone eventually gets out and moves on to jodo, the “pure land,” a peaceful place filled with flowers. One of the ways to do this, traditionally speaking, is getting a helping hand from the world of the living. The thinking goes that a thoughtful prayer for a departed soul may help free them from the “chains” binding them, eventually letting them to travel out of jigoku to jodo.

Place names evoking the concepts of sai-no-kawara, jigoku, and jodo can be found in nearly every mountain in Japan. Tetsuo Yamaori, a scholar of religious studies, calls it “the set of three,” and describes them as unique to the Japanese religious (and mountainous) landscape.

Tateyama is no exception. There is a long history of mountain worship here, going back at least 1,300 years. For much of this time Tateyama was widely considered one of the nation’s most revered pilgrimages, and many made the journey to Jigoku-dani in hopes of contacting departed loved ones. But in the 1870s, the Meiji government attempted to separate Buddhism from Shinto, with the aim of elevating Shinto as a state religion. This led to a misguided and vicious populist movement called haibutsu-kishaku: the elimination of Buddhist influences, which led to attacks on Buddhist temples and symbols.

I imagine that there used to be many spiritual effigies evoking the underworld in the area. But being Buddhist in nature, many were lost in this chaotic period in our history. Today, only a handful remain. The picture below was taken at Murodo-daira plateau, just a short walk from Jigoku-dani. You can see that many of the statues have been repaired at the neck. This is likely because they were beheaded during the 19th century purge. At some point after, gentler souls rescued and repaired them. The scars remind me a little of kintsugi, the art of repairing porcelain using gold. They evoke both the cruelty and the kindness of people. And also the resilience of our fusion of local beliefs, which are based on adding rather than rejecting different influences.

Still, someone felt compelled to put the little statues behind bars, presumably to protect them from any further vandalism. The rocks were left as offerings by visitors over the years. I added one, too.

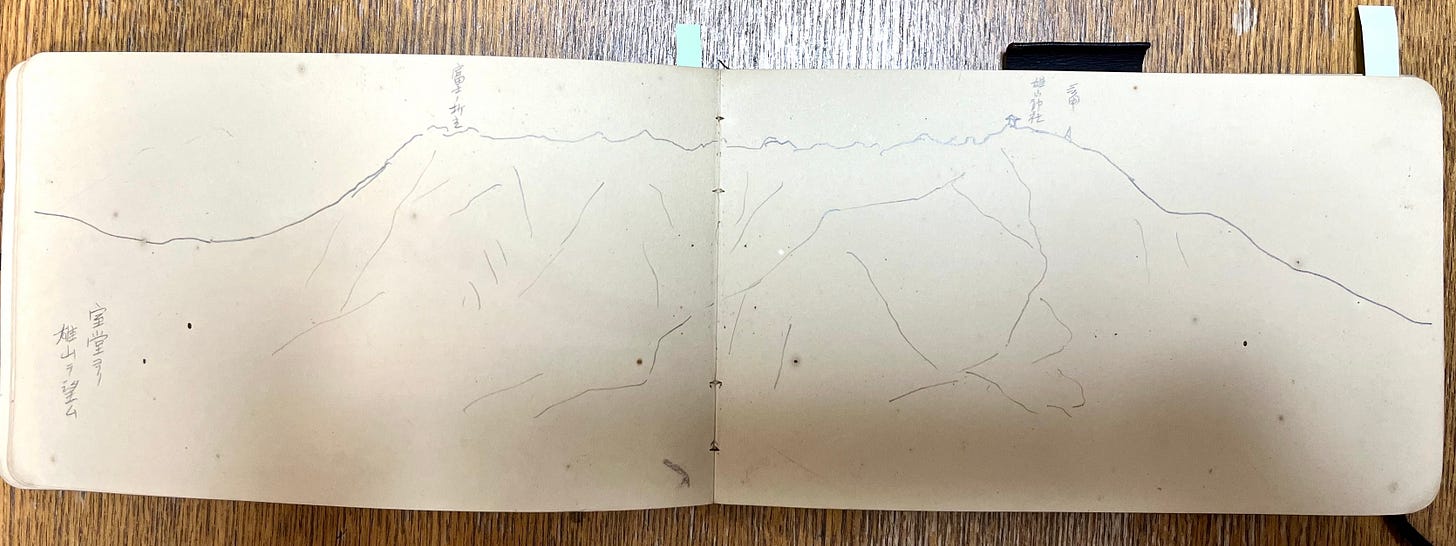

I’d wanted to go to Tateyama for quite some time. The reason being that my great grandfather visited there in 1908. As I wrote here, some time ago I inherited his diaries and papers. He was a scientist, an organic chemist, to be specific. But his hobby was the mountains. Actually, “hobby” doesn’t quite do it justice. He saw himself as an “alpinist.” Together with other like-minded sorts, he surveyed peaks and pioneered trails that would, years later, help establish mountain-climbing as a leisure activity in Japan. He passed away in 1941. I began following in his footsteps shortly after reading his diaries, which went into great detail about adventures in the mountains that unfolded many years before I was born.

In one entry, he wrote that “it was my visit to Tateyama that made me what they call a ‘mountain maniac.’” Those last two words aren’t a translation; they were written in careful English cursive. I suspect he learned this phrase from Walter Weston, a British missionary and mountaineer who popularized the phrase “Japan Alps.” They were both founding members of the Sangaku-kai, Japan’s Alpine Club. My great-grandfather’s diary entry continued that “the high mountains of Tateyama are rich in variation, setting them apart from other mountains in Japan,” and that “the view in all directions from Murodo, surrounded by high peaks, is absolutely thrilling.”

He was right. The view from what is now called Murodo-daira (plateau) is astonishing indeed. Murodo refers to an old wooden hut that pilgrims – and mountaineers like my great-grandfather – stayed in when they came here. Now it is a museum. I stood outside it, quite possibly in the very spot where he had once planted his own feet, and drank in the view. The three peaks of the Tateyama range towered over me like a gargantuan folding screen, nature’s art on a scale boggling human comprehension.

Later, back at home, I looked more closely at the diaries and found this sketch, penned in simple but meticulous linework. We really had shared the same patch of real estate, separated not by space but 117 years of time. Yet the mountains were totally unchanged, of course. On a geological scale, a century is less than a moment. It felt thrilling to make such close contact, even indirect, with my great grandfather in this way.

Tatetama consists of three peaks: Oyama (3,003m), Onanjiyama (3,015m), and Fuji no Oritate (2,999m). The trail led up from the plateau through all three, then descended a long slope called Obashiri (the “Big Run”) to return to Jigoku-dani. This route doesn’t seem to have existed in my great-grandfather’s era; his maps didn’t include the Big Run. Rather, he took an old pilgrimage route, much longer, via Mt. Tsurugi-dake, an imposing peak that symbolizes a mountain of needles widely portrayed in Buddhist hell-folkore.

There’s an old painting called the “Tateyama mandala” that portrays it in this way. Here’s a close-up: the spikes at left are Tsurugi-dake, while the more rounded one is Oyama. That’s Lord Enma, the judge of the underworld, at work at bottom right. That building atop Oyama looks to me like a place where kami, the native, non-Buddhist spirits of Japan, would be venerated. There’s in fact a Shinto shrine up there today. Seeing what might be one in a Buddhist painting shows just how thoroughly mixed spiritual traditions are here in Japan.

From my great-grandfather’s diary, I know he made the climb twice on consecutive days; the first ascent had been cloudy, and he wanted to make sure to see the view from the top, which he did on day two. We only needed one try. When we awoke on the day of our climb, a cloudless sky stretched overhead.

On the top of Oyama, there is an old Shinto shrine. The building is relatively new because it has been well maintained, but the shrine has been here for many hundreds of years. Because Tateyama was seen as sacred, in times of old pilgrims changed their straw sandals for clean ones well before they reached this spot. My great-grandfather wrote of “encountering the ugly sight of piles of discarded sandals” on the way here. Fortunately, there’s nothing like that marring the landscape now.

The interesting thing about this route is that each of the three peaks has a distinctly different sort of terrain. The first peak, Oyama, is a “typical” (at least in my mind) mountain, which is to say boulder-y. Onanjiyama has a jagged feel, as though the path has been sawn into the mountain. And beyond Fuji no Oritate, the landscape turns to sand.

All three tower far above Murodo-daira plateau, where our hike began. In the shot below, the blue lake is called Mikurigaike; the white patch behind is Jigoku-dani, stained by sulfur and obscured by rising gases.

Long ago, people made the long journey here to make contact with the souls of the dead. In a certain sense, I had done the same. I can’t say I felt as though I met my great-grandfather, but I certainly felt as though he was with me – or at least that I was with him.

When I was little, his oldest daughter, my great-aunt, often took my tiny hands in hers. “Your great-grandfather was a great man,” she would say. “His name is Mitsumaru Tsujimoto. Remember that.” She never went into any detail. Perhaps she thought I was too little to understand. But she felt it important to tell me this, repeatedly, in our all too short time together. The last link between her father’s generation and mine.

I’m sad we never met, never could have met. But I am grateful that he left so much behind. So many diaries, drawings, paintings, and articles. He wrote so passionately for so long about Japan’s mountains. He spent his life journeying among them. Now I follow in his footsteps, to see what he saw, and hopefully feel what he felt. I want to share it with him, in the only way I can, which is by leaving my own words behind.

That journey has just begun. And I can’t think of any better way to have started, than a little trip through hell – of the Japanese variety. I don’t know if my great-grandfather is there, specifically. But I do know he’s here, in the mountains.

I wrote a book about my experiences and adventures exploring Japan’s spirituality. It’s called Eight Million Ways to Happiness, and is due out in December of 2025. You can pre-order it here!

A beautiful travelogue, Hirokosan.

Congratulations on climbing Tateyama and your opportunity to “time travel.” Your grandfather’s line drawing was so precise and exactly matched your photo. All “mountain maniacs,” of which my wife is one, owe a debt to your ancestor and his generation of alpinists. I’m not nearly as experienced as my wife but I appreciate the culture of Japanese mountaineering that has grown up over the past 100 years. There goes Japan again, combining overseas influences with local traditions and sensibilities and creating something totally unique and cool.