Nakama

A story about unplugging and reconnecting in the mountains

There’s a word in Japanese that can be tricky to translate precisely into English: nakama. Depending on the context, it can be ally, comrade, colleague, or partner. A nakama is different from a tomodachi, a friend.

A friendship is a relationship among people who are drawn to one another for personal reasons. Maybe it’s a hobby or a shared sense of humor or what have you. Nakama describes a relationship among people who are collaborating for some reason, trying to attain some kind of shared goal. With all eyes on a shared prize, nakama relationships can be even more intense than friendships. I learned this myself, early one morning in May.

It was 6:45 A.M., according to my watch, when we reached the trailhead to Mt. Mizugakiyama in Yamanashi. We’d started early because it would take five and half hours round trip to the peak and back. The total distance wasn’t very long, just a little under five and a half kilometers. On flat terrain, a jogger could cover that in well under half an hour. But this wasn’t flat terrain. The peak stood far above, at 2,230 meters – almost a thousand meters above.

We’d done many day hikes, but never a peak this high. And Mizugakiyama was known for rough terrain; there were ladders and chains in some of the more treacherous sections. We chose this peak deliberately, as it sat next to an even longer hike I really wanted to do. A kilometer or so beyond the trailhead, the path forked. One way led to Mizugakiyama; the other, Mt. Kinpusan. But Kinpusan was a nine hour round trip. And at 2,599 meters, it had even more elevation gain. We figured we’d do Mizugakiyama to get the lay of the land, then return sometime in the future to climb Kinpusan.

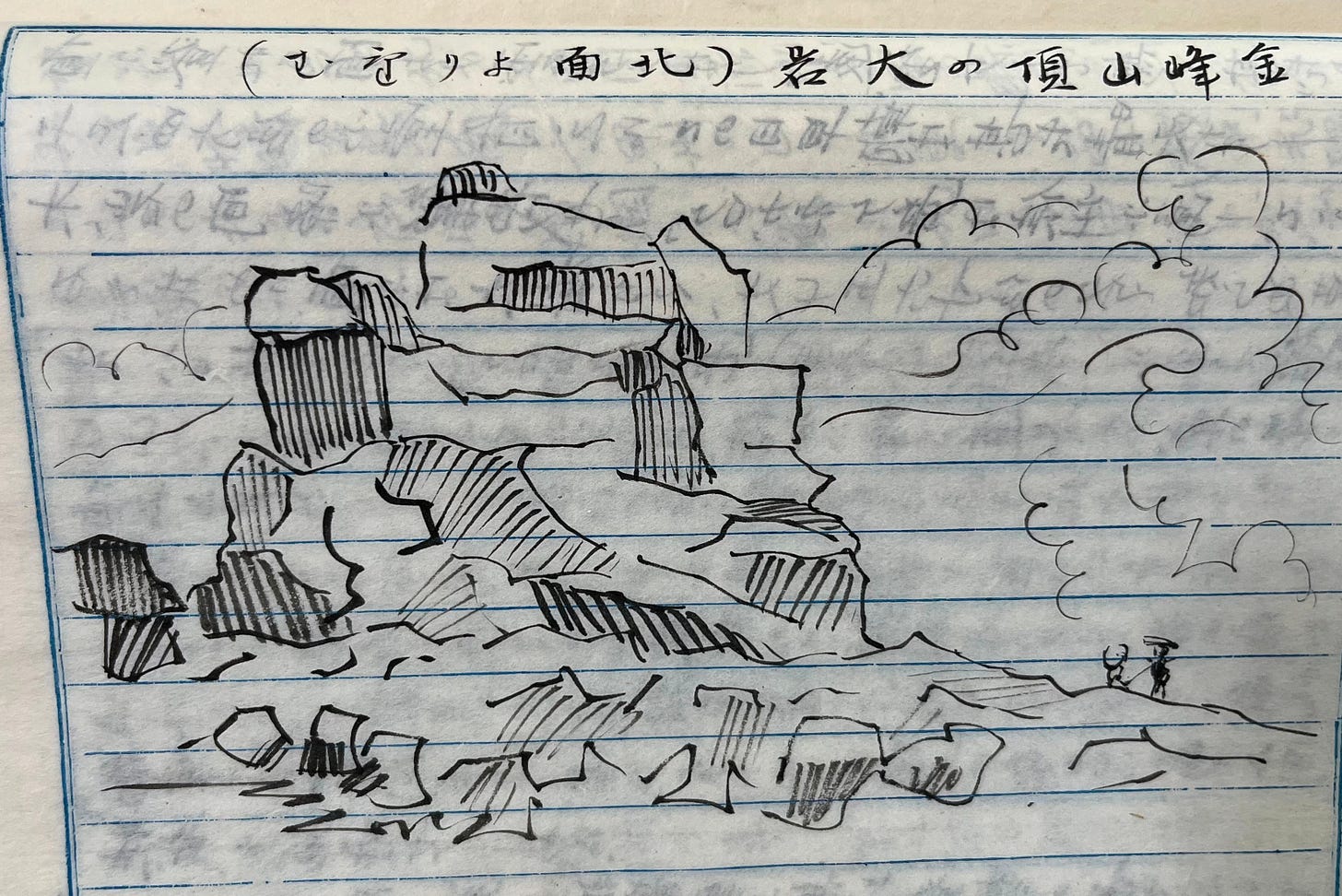

My fascination with Kinpusan came from the fact that my great grandfather climbed it, way back at the turn of the 20th century in 1900. He was a scientist and what was then known as an “alpinist,” a pioneer who helped establish mountain-climbing as a sport and leisure activity in Japan. I know this because he wrote many diaries of his expeditions, and I inherited them a few years ago. In their pages unfolded a story, one penned in words on washi paper, but also written in terrain, the stone and soil of my country. He climbed a hundred peaks over the course of his lifetime. And Kinpusan was one of his favorites.

“The mysterious formation at its peak cleaves the sky like a raised sword,” he wrote in one entry. “Clouds waft below. The grandeur of the sight stirs me to the point that I find myself shouting at the top of my lungs for joy.” The next page featured his inkbrush portrayal of the formation.

This must have been some view, I thought. So many of the things that moved our ancestors are lost to time. But not the mountains. To the mountains, the hundred and twenty-five years that had elapsed since my great-grandfather wrote his words and I read them was nothing at all. The more I read of my great-grandfather’s diaries, the more I wanted to know him. He had died decades before I was born. But here in the mountains, I thought, I might share the sights that made him shout for joy.

But I was no alpinist. Not yet, anyway. And so I resolved to climb a lower peak first. Neighboring Mizugakiyama. It was a start. And as a bonus, from its peak, I would be able to see Mt. Kinpusan’s from afar.

We made our way up the trail. Spring had already come to Tokyo, but here on the mountain it had only just begun. We ascended through forest peppered by the green flecks of young leaves. As the trees whispered their awakening from winter, the mountain azaleas shouted it, their blazing bright pink bouquets a treat for the eyes. As the sun rose the the air warmed and grew damper. It wasn’t cold enough to need a jacket, but that could change; the bus driver who’d taken us here had remarked that he’d heard there were still some snowfields up there.

Not even a half hour in, we encountered two young men who’d obviously started hiking a little ahead of us. Both looked to be about the same age – mid to late twenties? – but they were dressed quite differently.

One seemed an experienced hiker. He was dressed head to toe in functional gear: a breathable synthetic long-sleeve shirt, hiking pants, and high-cut boots. His large backpack had been tricked out with all sorts of customizations, like a pair of water bottles slung in holsters on the front for easy access, and his head was wrapped in a thin tenugui towel, like a craftsman. I’ll call him Bandana.

His companion, on the other hand, looked as though he’d just rolled out of bed, thrown on whatever he’d found on his floor, and headed out into the hills. He wore a plaid button-down shirt over bluejeans, the hems of which were tucked into his cotton tube socks. His feet were in sneakers. And his backpack looked like a kid’s bookbag. I don’t mean this as a fashion critique. You need to dress right for the mountains. (My friend Kiwi Yamabushi just wrote about this!) If it rains, cotton gets wet and cold. And if you encounter rough spots, you’re likely to twist an ankle in soft shoes. On the other hand, he possessed something no amount of money can buy: youth. Let’s call him Plaid.

As we approached the pair, I caught snippets of their conversation. They were friends, it seemed. Bandana was obviously the more experienced; he was giving Plaid all sorts of commonsense hiking tips. We said mutual greetings, as one always does in the mountains – konnichi wa! – and set off ahead of them. A little further ahead we stopped for something or another and they passed us. Konnichi wa! again.

Eventually, after about another half hour or so, my husband and I reached a camping area. There were Bandana and Plaid, standing at a picnic table, digging through their gear. By this time we felt almost acquainted, and laughed as we caught sight of one another. We set down our packs on the same picnic table to take a water break.

The camping area, which consisted of a small hut, a public toilet, and an open space for pitching tents, sat at the split in the trail. Left led to Mt. Mizugakiyama; right, to Mt. Kinpusan.

“Which way are you going?” asked Bandana, as he unfurled a large paper hiking map on the tabletop.

“Mizugakiyama,” I replied. He nodded.

“But I really want to climb Kinpusan,” I continued. “That is why we’re going to Mizugakiyama.”

He looked at me with a quizzical expression; he of course knew they were in opposite directions. I explained that we considered ourselves novices, and had hired a guide to take us up Kinpusan. The guide had suggested tackling a shorter hike first, to make sure we were in shape.

“But then it was all cancelled because of rain,” I explained. “I didn’t want to chance rescheduling, so I thought we’d just climb it ourselves on the next sunny day. That way, we can tell him we’re ready to hit Kinpusan.”

Bandana nodded as he listened. Then he looked straight at us and said, “We’re going to Kinpusan today. Want to go with us? I’m actually training to be a mountain guide. So the more the merrier.”

It was nice of him to offer, but there were two critical problems. One was that since we’d planned on a much shorter hike, we didn’t have enough water. The other was the bus, which we needed to catch to get back to the nearest station. If we missed that, we’d be stuck.

When Bandana heard this, he broke into a smile. “I’ve got you covered. I brought way too much water – I wanted the extra weight for training. And I drove us here. So I can give you a lift back to the station!”

My husband and I exchanged glances. This was so… irregular! Everything is so planned out these days, scheduled, in chats and emails and things. The organic-ness of this interaction took both of us by surprise.

“Are you sure?” I asked Bandana. “Like I said, we’re novices.”

“So’s my friend!” he said, pointing at his buddy. “This is only his second hike.”

“This is your second hike?” I asked Plaid. “Where was the first?”

“Mount Fuji,” he answered. This made us all laugh, because that’s the tallest peak in all of Japan. But then I realized something: my great-grandfather’s first climb had been Mount Fuji, too. That was the mountain that had sent him off on a lifetime of climbing. Maybe this young man was making the first steps on his own journey.

“I have just two conditions,” said Bandana. “If it turns out that we aren’t fast enough to make the summit, I’m going to make a call that we turn back. And two, if we hit a snowfield, we’ll turn back there too. We don’t have the gear to cross safely.”

We nodded in eager assent. In fact, his willingness to turn back put us more at ease. I’ve never been particularly goal-oriented when hiking. I don’t see reaching a summit as “bagging it” or “conquering it” or anything like that. I don’t feel bad if weather or something makes me turn around. For me, it’s all about spending time on the mountain. With the mountain. Bandana seemed to feel the same.

So the four of us shouldered our backpacks and set out. It felt like a moment – no longer were we four strangers, but a single group. It was a little like a real-life RPG video game: Hiroko and Matt joined the party! I could almost hear the symphonic fanfare from Dragon Quest in my head.

We were nakama.

Bandana turned out to be an excellent guide. He put us on a schedule of breaks every forty-five minutes or so, whether we were tired or not. Every time he’d fish a baggie of trail mix out of his pack and dispense it in handfuls, like a mother bird feeding her chicks. At first I thought he was doing this out of courtesy, and so after the first time I reflexively declined out of politeness. We were eating all of Bandana’s food! But he wouldn’t hear of it.

“People don’t realize how many calories they burn in the mountains. It’s just as important to eat along the way as it is to stay hydrated. That’s why I brought this!” Bandana slid a half-liter plastic trail bottle out of his backpack, filled with more dried fruit and nuts. “It’s my own recipe! I get the dried fruit in bulk from a local supermarket.”

We talked a lot as we walked. Bandana taught us how to tie our shoelaces to better support our feet in our boots. How to adjust our backpacks’ straps to better distribute their weight. When we encountered a stretch of boulders, he showed us how to navigate them safely, with three points of contact -- one hand and two feet, or two hands and one foot – at all times.

But my favorite part was the map. Most hikers rely on smartphone apps these days, and they work really well. But Bandana stressed the importance of knowing how to read a physical map. He’d unfurl that big topographical map on breaks, and show us how to match the concentric contour lines to the terrain around us, how to gauge travel time, how to double-check that we were where we thought we were.

“If you know how to read a topographical map,” said Bandana on one of these stops, “you can feel like you’re climbing even if you’re sitting at a desk. It’s chikei-moé,” he laughed, which might translate into a fetish for terrain. I laughed too. But then it struck me: with my great grandfather’s diaries I’d inherited a huge number of his old maps. I’d wondered why he had so many, even of mountains he’d never actually climbed. But now I knew. He could read them, literally conjuring the peaks in his mind from their two-dimensional contours on the page. How many times had he sat at his desk imagining the climbs ahead, or the climbs of old, or the climbs he would never make? It made me feel a little closer to my great-grandfather. As though we might be nakama as well as relatives.

Eventually, our party reached the final pitch to the summit. Up ahead, I could make out a massive pile of boulders. It was the “mysterious formation” of my great-grandfather’s diary! It looked so close, but we knew from reading the map, and the look of the steep slope leading away from us, that it lay at least another forty-five minutes ahead. Bandana suggested we take a final break.

Now it was my husband’s and my turn to play host. We had purchased bento lunches, and each came with two traditional onigiri – riceballs with pickled plum fillings. We offered to split them with Bandana and Plaid so we’d each have one. They tried to refuse, but this time we wouldn’t have it. We’d come all this way together, sharing Bandana’s knowledge, not to mention water and trail mix. It was the least we could do. We sat there, gazing up at our destination while eating shared rice balls. We were nakama, a bond forged by mountain magic.

We ate quickly and made the final ascent. We passed glorious stone cliff faces along the razor-like ridge leading to the summit. And before long, I found myself standing before that “mysterious formation” on the peak of Mount Kinpusen: Gojo-iwa. It was a beautiful day. We were blessed with 360 degree views of the Central and Southern Japan Alps and the Yatsugatake range. As I stood there, in the same spot my great-grandfather had more than a century before, I understood why he’d shouted for joy. Now I shouted, too.

We snapped photos of each other on the summit and made our way back down to the trailhead. We talked about many things over the three or so hours it took. But it wasn’t until we returned to the split where we’d first made our pact to climb together that I thought to ask a question. A question I hadn’t needed to ask, because we were nakama. But now we were something more. I turned to Bandana and Plaid.

“I’m Hiroko, and this is Matt. What are your names?”

And so a group of nakama became friends.

I wrote a book about my experiences and adventures exploring Japan’s spirituality. It’s called Eight Million Ways to Happiness, and is due out in December of 2025. You can pre-order it here!

I was very surprised, and humbled, by the mention, but not surprised at all when you said plaid was wearing jeans! It was like I was there!

Such an entertaining read, Yoda-san - thank you, and many congratulations on your forthcoming book!