Plum Rain

Monsoon season is supposed to be the cool before the summer. But things are changing.

The Japan Meteorological Agency has announced that tsuyu, Japan’s “rainy season,” began June 21st in Tokyo, several weeks later than usual. Some people seem to really dislike the rainy season, but not me. When I heard the news, I opened the window, looked up at the sky, and shouted “finally!” The reason being, it has been unseasonably hot this year. Even today as I post this, there is a heat stroke advisory. This is odd weather for June.

Tsuyu is, traditionally, akin to the line between spring and summer. Generally, it is cooler before the rains, then sweltering after. This year, however, things played out differently. Spring ended and temperatures spiraled up and up, with some days feeling like midsummer, months early. The hydrangeas, a typical June flower, bloomed early, and I watched with sympathy as they drooped low, as though begging for rain. Poor things. And June is the traditional month for planting the rice paddies. Are the farmers okay, I wonder?

Tsuyu is commonly translated as the “rainy season” in English, but in fact June isn’t the time Tokyo gets the most precipitation. It is actually September and October when the most rain falls by volume. When I saw those meteorological statistics for the first time, I was shocked, because I always associated rain with June. I’m not alone, because come June stores begin selling all kinds of raingear, every year’s patterns and designs changing with the fashions – a silent but colorful signal that it’s time for all of us to get wet. Flower shops put out the hydrangeas to brighten gloomy days. When I was a little girl, the concept of “June brides” arrived with fashion magazines. It sounded nice, but I also recall people wondering: who would want to get married in the rain?

June may not get the most precipitation, but it is the month with the highest number of rainy and cloudy days. In other words, it’s a month of humidity. Today, tsuyu is written with the characters 梅雨, literally “plum rain.” This is a reference to the 72 micro-seasons, specifically the one called “plums ripen and yellow.” But there’s something interesting about this. Japan imported the concept of the 72 micro-seasons from China. They didn’t write this one with the characters we use today. Instead, they called it 黴雨, which means the “mold rain.”

We all know that when the weather grows humid, mold grows like crazy. Making sure to ventilate closets and rooms, mop up wet areas like kitchens and bathrooms frequently, and being extra careful about food poisoning with bento boxes are so common sense as to be almost slogans of tsuyu in Japan. I follow them too – especially the food one. It amazes me how quickly a fresh loaf of bread will develop black spots in the rainy season compared to drier ones.

But perhaps calling rainy season the moldy season felt too direct, even uncomfortable for us. At some point, we replaced the kanji for “mold” with “plum” to make the name more poetic. Then they gave it a Japanese reading, tsuyu, derived from the word tsuyu-keshi, a now archaic adjective meaning “humid.”

Incidentally, pickled plums are a traditional food of the tsuyu season. Umeboshi, as they’re known in Japanese, are known to possess antibacterial properties – in other words, they help prevent food poisoning. How fitting that pickled plums are the best thing to eat during the “plum rain!” And in another connection to that calendar of old, it’s also said that fully-ripened yellow plums are the best for making the tastiest umeboshi.

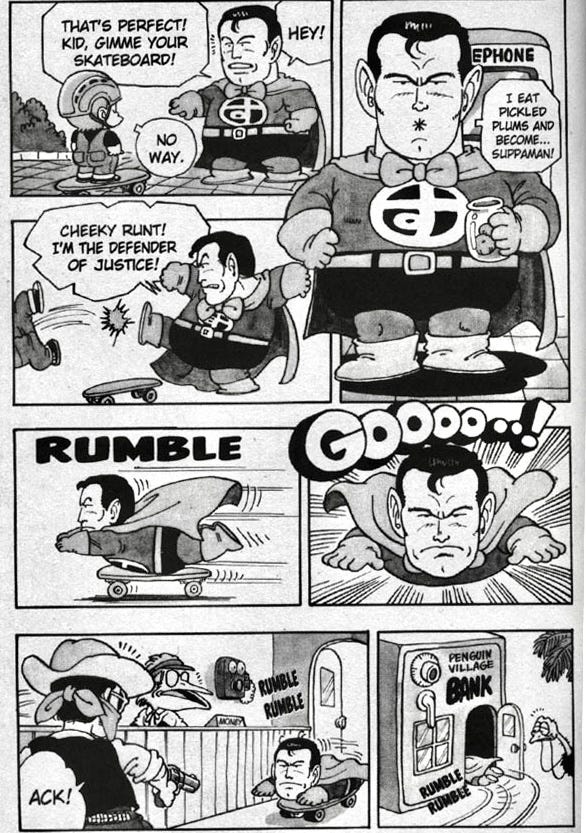

To Japanese, pickled plums are a kind of “superfood.” Their citric acid is said to ward off fatigue, so warlords and ninja carried them into the field when they went off to battle in times of old. Sweeter, honey- pickled plums are widely available today, but the traditional umeboshi are very salty and very sour. Seriously, even just thinking about them makes my lips pucker up. This aspect of the pickled plum was a major plot point in the late Akira Toriyama’s manga series Dr. Slump. One of its recurring characters is named Kenta Kuraaku, an ordinary salaryman with a secret. Whenever he pops a pickled plum into his mouth, he transforms into “Suppaman,” which sounds suspiciously close to “super” but means “sour” man, complete with puckered mouth.

As far back as I can remember, tsuyu season was like a month-long break before the heat of the summer. April is the month when the cold of winter fades, and flowers start blooming everywhere. May is when the temperature gradually warms, nourishing the growth of grasses and leaves. Then tsuyu hits in June. The temperature drops, like nature putting the brakes on to slow the seasonal change to summer. But things have changed in recent years. Sunny days, even spring ones, can be extremely hot. And when it rains, even outside of rainy season, it can be torrential, even causing floods. Things seem to be getting more extreme, less balanced.

And right now, as I write these words, Nihon Keizai Shimbun is reporting that Japanese apparel retailers are moving toward a five season model: an “early summer” in the traditional months, and a “second summer” playing out in September. I have to say, it’s kind of eerie. I often see cloudy or rainy weather described with negative terms, such as “dark” or “gloomy,” but these days, I appreciate them all the more, because I see them as part of the normal, natural cycle. It’s times like these that you really understand how raindrops are literal treasure from the heavens. I hope it rains again soon.

I lived in Japan over 50 years ago and your article brought back the taste of sour plums. I also make plum wine while I was there and carried the jar with me through 8 years of moving from place to place until the wine had matured. It was wonderful. I love Japan.

I like the rain, too. Especially in gardens. Okayama’s Korakuen garden was gorgeous yesterday.