When you wish upon two stars

Tanabata is a bittersweet story, but a fun festival. Here’s the history!

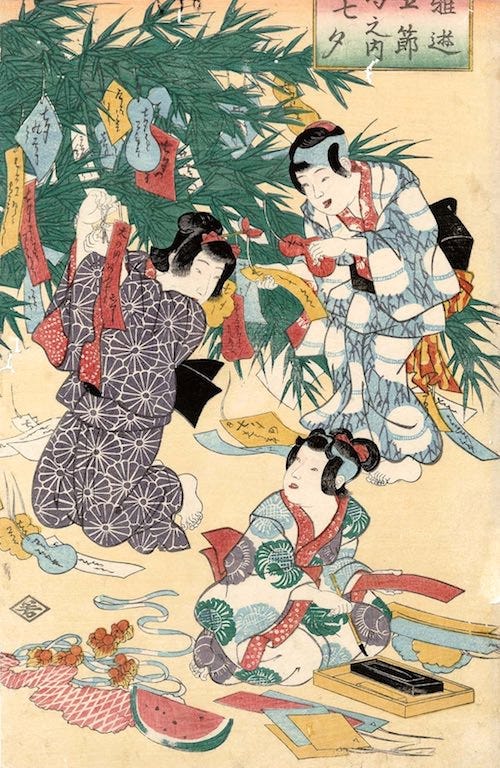

July 7th is Tanabata – the “Star Festival.” Japan celebrates this old tradition in many different ways. But the basic concept is the same. People put up stalks of bamboo, then decorate the branches with colorful handmade paper ornaments, like streamers and folded origami cranes and tanzaku. These last are narrow strips of paper for people to write down their wishes, in hopes the stars may grant them. At this time of year, you can see the decorations in all sorts of places.

Kappabashi, the kitchenware district of Tokyo, has some particularly spectacular (and crowded!) Tanabata displays this weekend, but you can see them across Japan: at shrines (here’s a video I took at Tsurugaoka Hachimangu), schools, supermarkets, shopping arcades, apartment lobbies, houses — anywhere and everywhere people gather, really. It’s summery fun, but I suspect most visitors to Japan don’t know the story behind the streamers, so to speak. So I wanted to talk about it here.

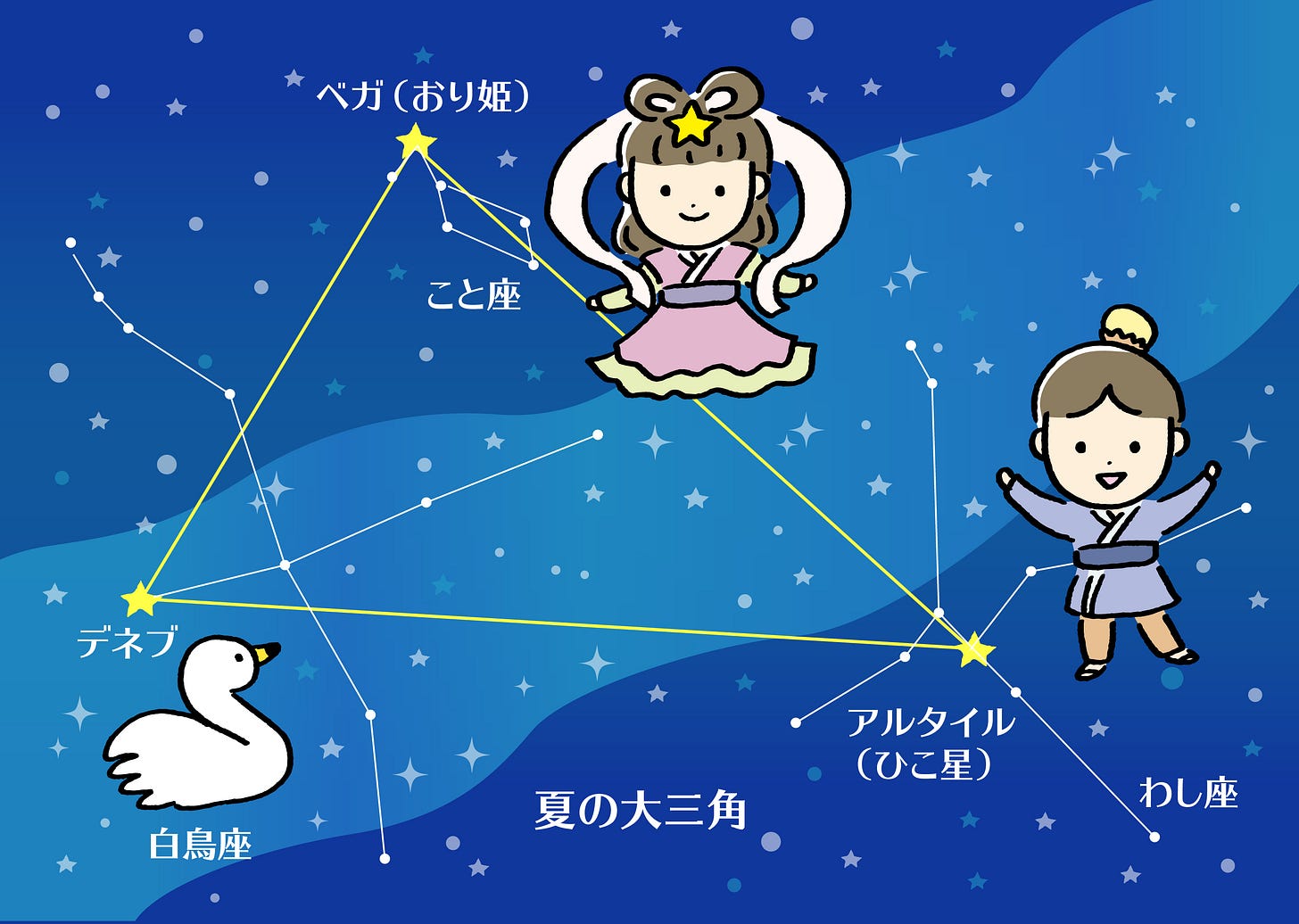

A “Star Festival” sounds almost like science fiction, but Tanabata is a love story. It features two literal and metaphorical stars: Orihimé, the “weaving-princess,” and Hikoboshi, the “shepherd star.” They lived and worked on opposite “banks” of the Milky Way (which is known in Japanese as Ama-no-gawa, “the river of the heavens.”)

But one day, Orihimé’s father, the Heavenly Father, arranged for the two to meet. It was love at first sight, and the pair quickly married. But lost in the depths of their heavenly honeymoon, they began neglecting their work. This infuriated the Heavenly Father. He separated the young couple, placing each on opposite sides of the Milky Way, and forbade them to meet save for one day a year: the seventh day of the seventh month. That day is Tanabata.

The origins of the story can be found in the Chinese Qixi Festival, which Japan adopted over a thousand years ago as a ritual ceremony for the Imperial Palace. A straight reading of the Chinese characters would have given a reading of shichi-seki in Japanese, but instead the name was localized into Tanabata, which is another word for “weaver.” The nobility soon adopted the custom for themselves, making wishes to Orihimé for better sewing skills — an absolute necessity of life in an era before mass-produced clothing.

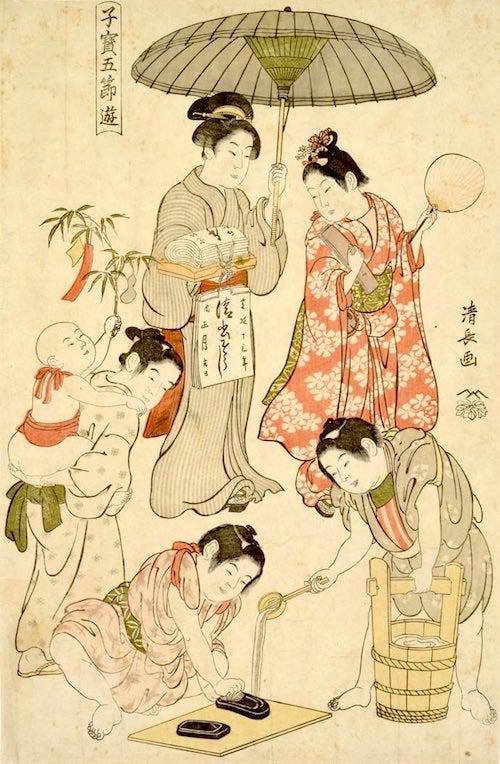

It wouldn’t be for many centuries, until the Edo era, that Tanabata took off among the commonfolk. In Buddhist terakoya schools, a precursor to the modern educational system, children were encouraged to pen wishes to improve their reading and writing on long slips of paper – the origin of the tanzaku streamers I mentioned above. This became associated with another tradition, of washing your inkstone on Tanabata – a gesture of thanks to the tools that help us write, read, and learn. These days, like most people, I do all of my writing on my computer. But writing this out makes me want to kick off a new tradition of cleaning my screen and keyboard on Tanabata.

In the print below, you can see all sorts of paper ornaments. Each has a specific meaning, and many were spiritual in nature, wishes for good luck. For example, the streamers being prepped on the ground represent yarn or thread, for sewing skills. Gourds are wishes for health. Nets for big catches of fish. Watermelons for an abundant harvest. Many of these specific meanings have been lost, or perhaps better to say aren’t widely used anymore. But the idea of making and hanging paper ornaments on boughs of bamboo remains.

When I was young, I would celebrate Tanabata at home. My mother would bring home boughs of bamboo, I would decorate them, and we’d put them in the dining room. I thought the display was pretty, and enjoyed folding origami and such for the decorations. But I always hesitated to make actual wishes to Orihimé and Hikoboshi. The reason being, I felt bad for them!

Even as a little girl, I thought their story was kind of brutal, and it didn’t feel right asking favors from people suffering so. I think I was kind of unusual in thinking about them this way. But time moves so slowly for children. A year seemed almost forever to a little girl like me. How could they tolerate being apart that long? And their long-awaited rendezvous was also tied to something totally beyond their control: weather.

The legends said that Orihimé and Hikoboshi could only re-join in a clear sky. If clouds obscured the Milky Way, the star-crossed pair would have to wait another year, hoping for a clear sky next time. It was sometimes said that rain on the 7th was tears shed by the frustrated couple. The thing is, July 7th is right in the middle of the Plum Rain – rainy season. As far back as I can remember, Tokyo has almost always been cloudy or rainy on that day. So why on Earth would people in times of old pick this day for a spiritual tradition that depended on clear skies? I looked up some weather statistics, and it seems the chances of a clear day on July 7th are only something like 30%. This couple is almost destined to “cry” year after year. How sad is that?

Much later, I learned why such a cloudy time had come to be associated with Tanabata. It’s all due to Japan switching from its traditional lunisolar calendar to Gregorian in the 19th century. Until then, Tanabata on the 7th day of the 7th month lunisolar, which corresponds to August on modern calendars. There is a much higher chance of a clear night then. Even more importantly, the Summer Triangle can be seen in the northern celestial hemisphere in August. The Summer Triangle consists of the stars Deneb, Vega, and Altair, and Orihimé and Hikoboshi are avatars of Vega and Altair.

I looked things up on a modern lunisolar calendar. It seems this year’s July 7th corresponds to August 10th. So I’m going to shift my wishes ahead a month. Will it be clear that night? Will Orihimé and Hikoboshi meet again? Watch she skies, and cross your fingers for them. It’s the season of wishes, after all.

I enjoy the Japanese words for concepts or situations for which the English language has no parallels.

Mahalo plenty for this article! 🙂

I vaguely remember hearing about Tanabata when I was young. I'm going to share this with my nieces and encourage them to make a streamer to hang, that will be a fun summertime activity for them!